The Bridge

Michael Maltzan designs spaces where communities come together to share their stories.

IN THE 1932 MOVIE I Am a Fugitive from a Chain Gang, the protagonist, a decorated World War I veteran returning home to resume life as a civilian, gazes out his office window upon the bustling construction of a new bridge in downtown Los Angeles. Dazzled by the engineering feat, he neglects his banal duties as an office clerk and each day explores the bridge, admiring the impressive steel arches that would, in the real world, go on to carve their unique history in LA’s skyline. This would mark the first of many appearances for the iconic Sixth Street Viaduct in film and television. Arguably, the most widely known is its cameo in Grease, when John Travolta roars along the cement-covered LA River in the movie’s culminating drag race.

Unfortunately, the viaduct had been plagued from its birth by a fatal alkaline in the cement that steadily degraded its structural integrity. It became increasingly clear that demolishing the original structure and starting from scratch was inevitable. In 2016, after 84 years, the viaduct met its demise, beginning a new chapter for an infrastructure project as rife with challenge as it was with opportunity. When Michael Maltzan BArch 85/P 24 was chosen as the architect to lead the viaduct overhaul, he drew from lessons he learned at RISD.

“This may be a form of cultivated naivete, but when I approached this project, I really went back to something that RISD instills in you as a ‘maker,’” says Maltzan during a Zoom call from his office in LA.

“RISD taught me to push aside the idea of a preconceived solution, and to believe that the most important things are to begin and to trust your instincts and your experiences to help guide you through that process.”

The roughly $588 million project is said to be the largest bridge project in the history of LA. It was funded by the Federal Highway Transportation Administration and the California Department of Transportation, as well as city funds. The viaduct, which connects the downtown arts district to Boyle Heights, offered a tangible opportunity for Maltzan and his collaborators to craft a very literal bridge between communities, and to do something that has grown increasingly rare in the United States, post–World War II—build infrastructure that can be a source of shared pride among the people who use it and live near it.

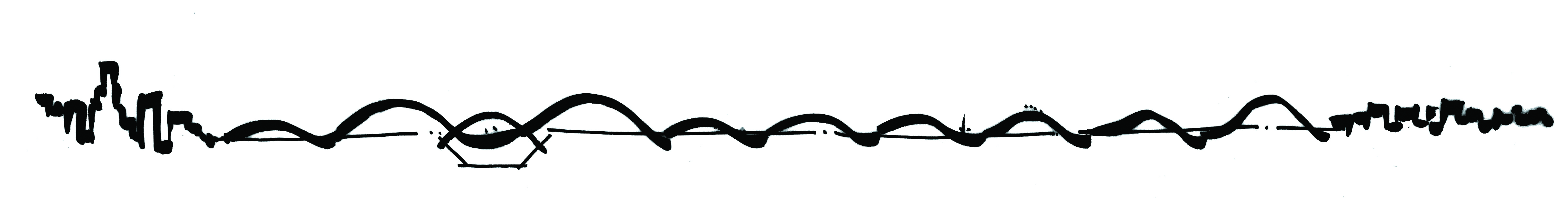

After a few years of construction, the new viaduct finally opened last year to universal acclaim and widespread excitement among LA’s residents. A safer, more modern, and more accessible structure, with green spaces (a twelve-acre public park below the bridge) and accommodations for bicyclists and people with disabilities, the new bridge strikes a balance between the competing forces of nostalgia, progress and potential. Maltzan made sure to include arches that pay tribute to the most distinctive characteristic of the original structure.

Also known as The Ribbon of Light for its multiple arches, which light from below, the viaduct has become a destination spot, attracting walkers, runners, bicyclists, skateboarders, families out for an evening stroll, and photographers looking to capture images of the arches and LA skyline backlit by the setting sun. “The bridge is really meant to be a civic armature, to turn infrastructure into something that weaves together the city ... [and] connects communities,” Maltzan says.

The Sixth Street Viaduct also represents a return to an architectural philosophy dominant in big cities prior to World War II, when designers were influenced by the City Beautiful Movement—design and urban beautification to inject a sense of humanity, creativity and cultural pride into areas of cities where residents had too often been forced to endure overcrowded tenements and shoddy planning.

“After World War II, there was a diminished sense of a collective physical, civic space, particularly as so many people fled the cities for the suburbs. That’s starting to change, and you can see it in projects in New York City and in San Francisco, and now here in Los Angeles with the Sixth Street Viaduct,” Maltzan explains.

“There’s a renewed understanding that infrastructure doesn’t have to be the thing that tears cities apart and separates communities but can be something that in fact weaves those communities and cities back together again.”

Road to RISD

Maltzan says he has tried his best to recreate the dynamic he experienced at RISD within his firm, Michael Maltzan Architecture. That cross-pollination of different creative disciplines that RISD offers prepared him for the wide range of professionals he collaborates with as an architect. He largely credits his experiences at RISD for helping shape his unusually diverse portfolio, from breathtaking single-family homes to affordable multi-tenant housing to art museums and large-scale infrastructure challenges like the viaduct.

“There are so few places in the world where you can feel the collective sense of purpose that you feel at RISD, driven by a commitment to making things,” Maltzan says.

“I have always been attracted to that amazing culture where everybody is committed to making a creative contribution, and it all goes back to my Freshman Foundation at RISD, where painters, sculptors, graphic designers and architects were connected by the fundamental process of learning how to see something in your head and then making something from that which is meaningful to you,” he adds.

An enthusiastic art and drawing student in high school, Maltzan began his journey to RISD when he was working part time for local architects who had all gone to RISD and eventually encouraged him to apply.

“After visiting the RISD campus, I came away feeling like it was a culture and a place that I felt connected to in a way that I had never felt in any other areas of my life. After that first visit, I couldn’t get the school out of my mind,” he recalls.

Civic Spaces

Maltzan’s firm is a modern example of the impact architecture can have on the greatest social challenges of today. While the industry has a long if somewhat uneven history of trying to address global issues surrounding social justice and inequality, the notion of community has been present in the industry since the transitional era between the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, when architecture throughout Europe was largely focused on creating innovative forms of housing to address the emergence of increasingly undeniable socioeconomic forces, such as a migration from rural areas to bigger cities. Many projects were aimed at affordable housing in which thoughtful architectural design had seldom if ever existed.

Despite the diminished capacity for civic spaces in the United States post–World War II, there were progressive initiatives, such as California’s Case Study House Program, that sought to harness in a domestic capacity the materials and technology that had emerged during the war, especially new technologies of construction and the use of glass, steel, reinforced concrete and synthetic materials. The program brought together architects and designers to create innovative, affordable single-family housing for soldiers returning home. By the 1960s, the environmental movement impacted the building boom and began to influence modern architecture and design in a manner that has helped pave the way for modern sustainability philosophies and methods—the advent of the first solar buildings, for example, were born out of this movement.

“Architecture’s legacy of deep involvement with social justice issues helped lay a foundation for the moment we’re living in now, where many of these concerns—[sustainability, affordability, justice]—have become not just pressing, but actual crises,” Maltzan says. “So it’s only right that architecture would be called on to grow its responsibility and relationship to these challenges.”

This is nothing new for Maltzan. When he opened his architecture and urban design firm in 1995, there was a sharp focus on promoting the philosophy that architecture can play a vital role in creating progressive change, particularly when it comes to shared spaces and how people interact with them. Maltzan says his firm is committed to meeting challenges in many different contexts to confront cultural, social and political struggles. His projects are consistently informed by an interest in the space that is defined by the buildings and how people engage with them, not solely by the sculptural forms of the projects.

“What motivates me is what causes individuals or communities to make connections and the ways in which architecture allows separated people and constituencies to be woven together,” he says.

That sentiment may be commonly expressed in architecture as an industry, but putting it into practice requires tremendous research, collaboration and humility, which Maltzan achieves by working closely with the communities that will actually be engaging with his work—an obvious but often overlooked layer to civic and infrastructure projects. Maltzan believes that comes before the technical and cross-disciplinary broader vision.

“We always begin by developing a conversation around what the common ambitions are,” Maltzan explains. “We find the common purpose before we talk about the specifics of all the different collaborators and technical necessities.”

Maltzan doesn’t consider himself an artist, but thanks to RISD his work is more heavily influenced by artists and art history than by architects. He believes that despite their vast differences, the connective tissue binding painters, sculptors, graphic designers and architects is the passion to express something of consequence about the world they live in.

His appreciation for the arts helps shape how he selects some of his most exciting projects. He’s looking forward to working on a performing arts complex at the Rochester Institute of Technology in New York, which will include a 750-seat theater and a 1,200-seat symphony hall.

“I have always loved performance spaces since my beginnings in architecture, and these are two theaters that are very important to me,” explains Maltzan. “While we’ve done some smaller theaters, I haven’t had an opportunity to work on one at this larger scale, and they’re such special spaces. If you look at the history of theaters, they hold an extraordinary place in architecture’s legacy; they are a place where people can connect.

“That act of coming together in a collective way is where architecture can be at its very best, and so this [performing arts] project means a great deal to me.”

Words by Doug Daniels

Photos by Páll Stefánsson