Rise of Artificial Intelligence

In 2022, we woke up to a new technology that—like the iPhone, the internet, industrial robots and the atomic bomb—will irrevocably change our world: generative AI in the form of ChatGPT, DALL-E and MidJourney, among many others.

ChatGPT is a chatbot developed by OpenAI that seems able to understand what we write to it and responds in ways that appear to be almost human. But what is generative AI for images? It’s a modelbased description of all possible images, extrapolated from the analysis of a mind-bogglingly large number of images culled from the internet. This is similar to the way we predict weather: we have many, many weather stations around and in orbit, and we get data from them on a minute-by-minute basis. By using this data to develop mathematical models, we can predict the weather with pretty fair accuracy.

Generative AI develops its “understanding” of an image using the diffusion model. To be useful, each image has to have a natural language description of its contents attached to it. This is why the internet and the image databases of stock photo companies and online art presentation sites are essential to these images’ creation. At first, the model associates only the image—that is, its pixel relationships—with the description. Then the trainer adds a small amount of noise (blur) to the image, blurring it slightly, and the AI uses the description to reconstitute it. The process is repeated numerous times until the AI can rebuild the image from pure noise.

Metaphorically, it looks at paint stains on a wall and hallucinates what it’s been told to. It has a very well-developed sense of the underlying pixel structure of images and builds from the pixels up based on the probability of one square of color appearing alongside another in images described in the manner requested. This is why the same AI is useful for unblurring photos, removing noise from images and video, and increasing the resolution of images that are too small for a particular purpose. Most smartphones use some form of image AI.

When this technology is applied to language, it can seem startlingly human and provide interesting and useful responses to various requests. In some amusing tests, ChatGPT has successfully rewritten the first chapter of Genesis in the style of a corporate memo and economic report in sonnet form.

When this modeling is applied to imagery, the language model applies its training to give the image model the structure it needs to generate the image requested. The results range from prosaic to astonishing. Some of the most beautiful examples I’ve seen recently are images of elderly people from Africa as fashion models in clothes derived from traditional styles and an imagined version of the 1982 Disney film Tron as though it had been designed and directed by the Chilean-French filmmaker Alejandro Jodorowsky in the 1970s.

None of the models, clothes, or sets are real. None are based directly on existing imagery, as a Photoshop creation might be. All were created through painstaking description and iteration. It’s worth noting that the creators of these images are both filmmakers, deeply knowledgeable in the aesthetics of film and already well practiced in getting the best out of AI image generation. That’s important, because getting a good image out of the current AI image generators is nowhere near as simple as making a general request.

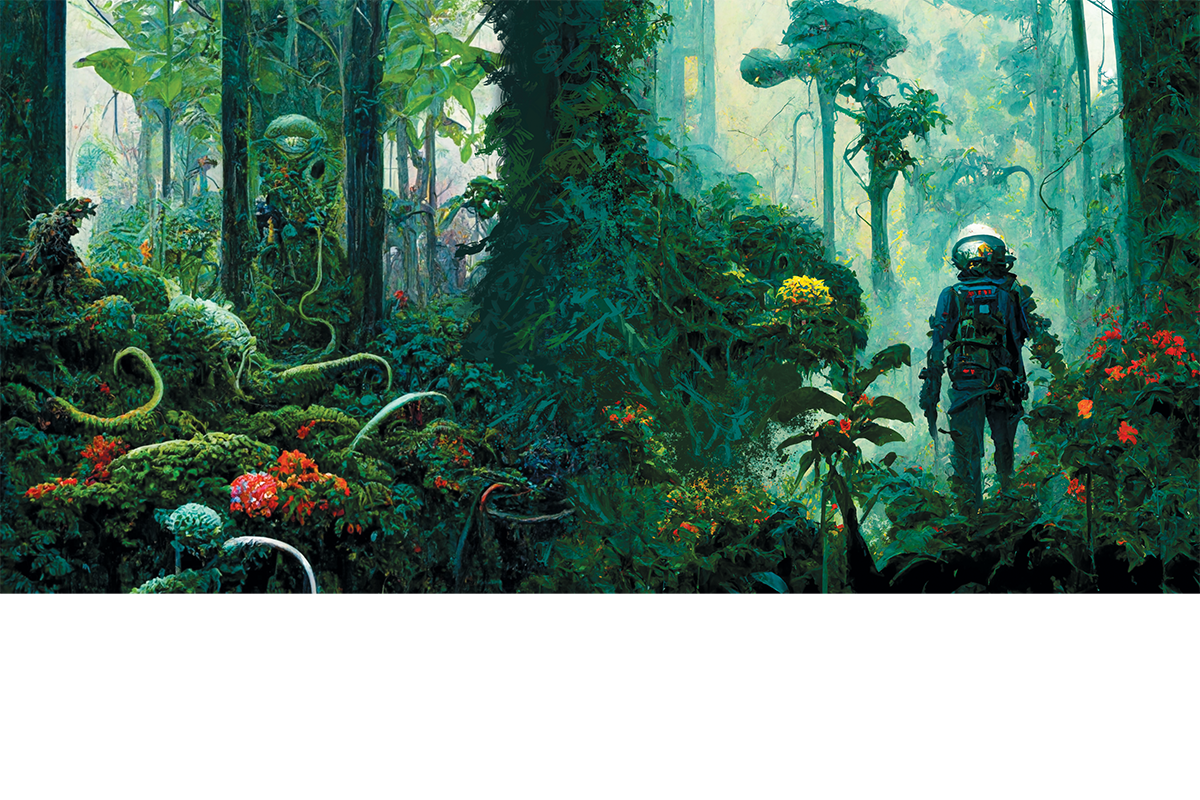

One of the most popular AI image generators is MidJourney. I’ve experimented with it myself, using a science fiction–themed prompt to see whether I could create something suitable for the cover of science fiction novel (my previous profession). The prompt I used was “an alien jungle, fanged trees, poisonous flowers, humid air, a human in a space suit with a large gun against a tree, with a large, reptilian cat approaching threateningly.” The program created a quartet of images to choose from as well as a few simple buttons to allow for generating random variations of the images. Only one image contained a reptilian cat, and none of the images placed the astronaut against a tree. Nevertheless, the results were intriguing, and after four iterations, I had produced two images that I thought went well enough with each other to spend ten minutes stitching them together in a photo editing application. Total time it took: about forty-five minutes. Contrast that with the week or so it took me to paint in acrylics and oils the cover for the novel Signs of Life by Cherry Wilder, in 1997.

This technology is naturally causing alarm: to create high-quality images of sufficient specificity for commercial purposes with effectively no training is difficult enough to contemplate for people whose livelihoods depend on image making. Adding insult to potential injury is the fact that the models these programs consist of have been trained on images created by the very artists it threatens to make obsolete financially, if not artistically. Most of the AI image generation programs allow the user to specify the genre and even specific artists whose style the image should imitate. The most popular artist to emulate in AI art is Greg Rutkowski, a concept artist for a wide variety of fantasy games. His name had been used as a prompt to create AI art more than 93,000 times as of September of last year, comparatively early in the widespread use of the technology.

Victo Ngai 10 IL, the much-awarded illustrator and designer, has had her work used as a training model to create new “Ngais” that any artist or aficionado would say bear little resemblance to her actual work but that other people are using to create pastiches in sufficient quantity that they are appearing in image searches for her work. The prospect of losing control of one’s own images, brand, and livelihood is alarming enough that a number of artists have launched a class action suit against several of the companies that have made publicly available AI image generators, as well as several websites that without the artists’ knowledge allowed their databases to be vacuumed up for AI training.

AI image generation is going to change many aspects of how artists and designers do their work— in industrial design and architectural product visualization, illustration, filmmaking, visual effects, video games and Augmented Reality and Virtual Reality. Very little in the way the design business is done will be untouched. Some people will be hurt immediately, but others will find ways to continue and prosper. Rates for many kinds of illustration are already so low that it can be difficult to maintain a reasonable income—and income would certainly be forced lower or eliminated completely by a mechanical means of image generation. On the other hand, the use of AI in the ideation stage of the creative process can be a rapid way to generate, if not finished images, some refreshingly unexpected alternative concepts. AI generators are even developing the ability to infer a more complete version of an image from a sketch, allowing a more direct and rapid way to transition from an idea to a finished product. A number of commercial photographers are already supplementing their income by creating and uploading AI photography to stock sites. While effective in the short term, these efforts do seem to be creating an environment that devalues commercial photography.

AI presents difficulties for education and arts institutions. How do you prepare artists to prosper in an environment where opting out of AI is not an option? What sort of ethical constraints and human machine collaboration can be designed to optimize a thriving, healthy arts community? To what extent does generative AI undercut or, paradoxically, place a greater emphasis on highly developed craft skills and traditional media? There have been ongoing discussions throughout RISD and within most departments on the ways in which AI presents both opportunities and difficulties for educating artists and designers, and we are sharing policies and suggestions on a weekly basis. Considering how rapidly the technology is developing, educating for a world in which AI art is an intrinsic element of creative work is going to be even more of a rapidly moving target than the digital revolutions that came before it.

It’s probable that most of the commercial arts, at least in terms of volume, will be produced by AI within a decade or two, with only the most elite production handled by humans in collaboration with AI. Already, Netflix is using AI art in the production of animation backgrounds, and many people believe that a logical extension of video on demand is entertainment actually produced on the fly to suit particular tastes. AI-generated films would not require royalty payments or outlays for stars, directors or staffing.

As jobs in the arts change, so too will the motivation to pursue careers in art and design as well as the ways of monetizing the skills. Many of what are now considered foot-in-the-door jobs will be handled by AI. So, what will the aspiring illustrator, director, industrial designer or visual effects artist do in the future? Extrapolating from how the independent film and video game developers of today work, the answer is everything. Make the film. Make the game. Make the products. Then find someone to buy them from you if you can. This mode of production resembles that of the fine arts more than the contemporary commercial arts, and its precariousness and difficulty may dissuade people from attempting it as a full-time profession. However, given the ease and rapidity of production, people may find that they can be an experimental filmmaker for a few hours a week and produce epics. If a sufficient number of film buffs decide that those epics are meaningful to them, they will find ways to pay the artist. It’s likely that the commercial artists of the (near) future will be doing their art as fine artists have always done: because they have no choice, because it gives them joy, because they want to experience the result and no one else is making something just like it, and for personal development.

Words by Associate Professor of Illustration Nick Jainschigg 83 IL