Radical Generosity

Lina Sergie Attar worked to find shelter for those displaced by the recent earthquakes in Turkey and Syria, and her Karam Foundation continues to help refugees design their own futures.

Lina Sergie Attar MArch 01 stood before a towering pile of rubble, unable to fully absorb the destruction.

The Hatay Province in southern Turkey and its capital city of Antakya occupy a rich slice of human history, home to one of the Roman Empire’s largest cities and an early center of Christianity.

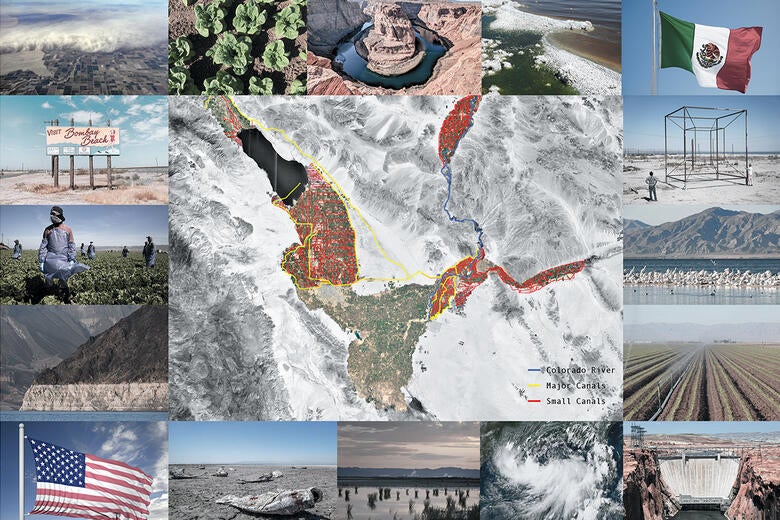

The area’s ancient churches, mosques, and other archaeological treasures have long been revered by scholars and laypeople. But many of them have been reduced to rubble after last winter’s devastating earthquakes in Turkey and Syria. The tragedy left nearly sixty thousand people dead and another 1.5 million homeless. The structural damage was breathtaking, with a price tag of nearly $110 billion.

But nothing compares to the human toll of the natural disaster for a population already suffering immensely from a man-made one. Turkey has seen a massive influx of refugees as the Syrian civil war rages on toward its thirteenth year, and the displacement of those fleeing war has now been immeasurably exacerbated.

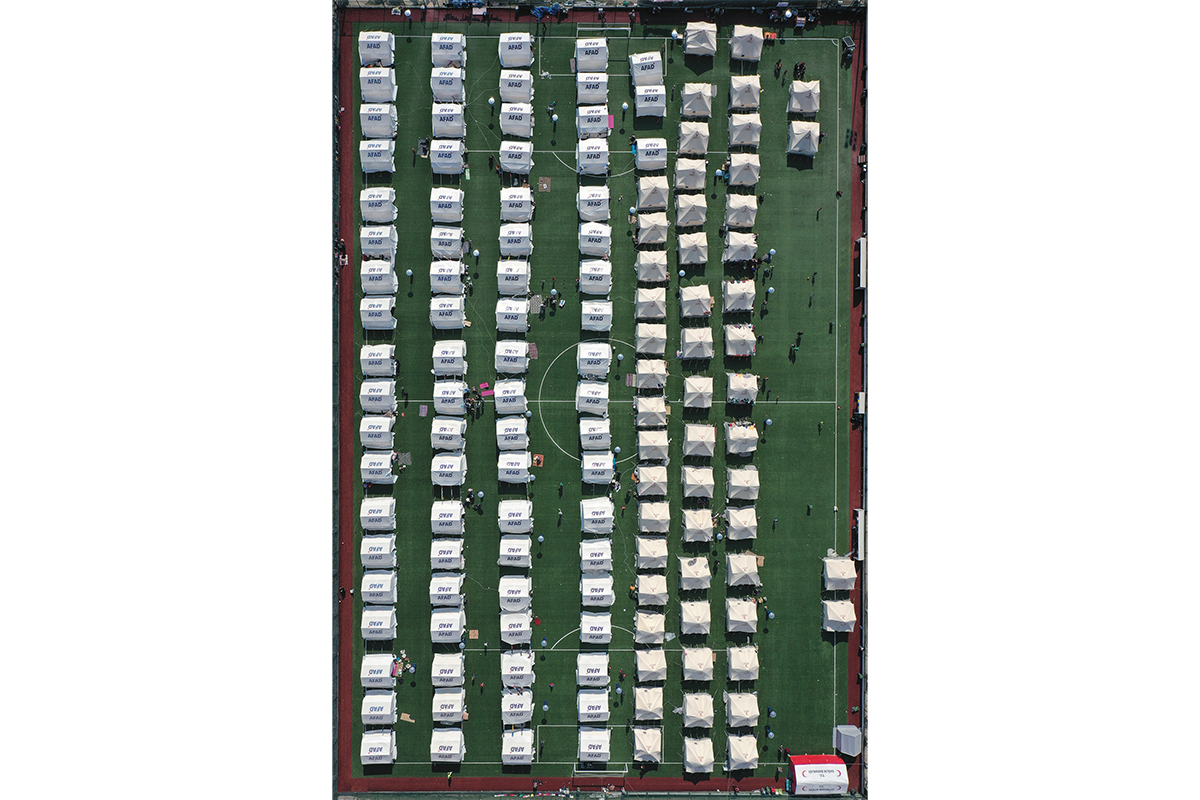

For Attar, a Syrian American architect and writer who founded and serves as the CEO of the Karam Foundation, this latest catastrophe poses fresh challenges for her refugee aid and educational organization. In the immediate aftermath of the earthquakes, Karam (which means “generosity” in Arabic) moved quickly to provide food, shelter and other necessities. It also helped connect struggling communities with mental health services.

The organization managed to distribute over 8,800 diapers, 2,000 bread bags, 1,500 bottles of water, 350 parcels of food, 250 thermal blankets, and 50 mattresses. Today the foundation supports a number of camps by serving daily meals to thousands of earthquake survivors, and it hosts pop-up tents offering creative and innovative activities, games and movie nights to help ease the suffering of the displaced children.

“I honestly have not been able to process the earthquake damage,” Attar says a few days after she returns home to Chicago from Turkey. “My brain kept telling my eyes, ‘You’re not seeing reality.’ It’s so heartbreaking to see all these peoples’ homes and lives completely wiped out overnight.”

Beyond providing food and supplies, Karam also stepped in to assist in a number of areas outside their typical purview, offering evacuation support, temporary shelter, and cash assistance to families in Hatay Province and Syria.

ATTAR HAS A DEEP affection for the people in the region she once called home. Her foundation, despite its recent short-term response to the earthquakes, is primarily focused on sustained long-term support of the refugee population. Karam currently has two community educational centers in Turkey, called Karam Houses, for young Syrian refugees displaced by the war.

“Our goal is to help shape ten thousand young Syrian leaders by 2028,” Attar says. “We define leaders as every young refugee we’ve empowered to either complete their higher education or learn the skills to secure dignified work,” she adds. “We’re putting them on the pathways to their full potential wherever they ultimately land.”

Born in the US, Attar moved with her parents back to their home country of Syria when she was twelve and stayed there through college before coming to RISD for graduate school. When she started her nonprofit in 2007, based in Chicago, she never imagined the organization would evolve into the highly impactful global force it has become.

The 2020 RISD Serves Award recipient, Attar was inspired by her father’s charity work in Aleppo, the Syrian city that erupted in revolution in 2011—a conflict that has now displaced more than fourteen million Syrian refugees. The revolution and continued civil war both raised the stakes and dramatically expanded the foundation’s potential reach.

“Initially, the idea was to focus mainly on the Arab American community here in Chicago and offer a new way of thinking about charity in a comprehensive and long-term way,” Attar says. “I was fascinated at the time by some of the emerging innovations in charitable giving, like microloans, that could help underserved or displaced communities not simply get the bare essentials but really rebuild their lives.”

Attar quickly decided she wanted to focus on Syrian youth and offer them opportunities to learn skills and develop creative and artistic talents in the foundation’s Karam House community centers. She believes her inexperience early on creating and running a nonprofit was an unexpected advantage. While other nonprofits often follow a cookie cutter approach, Attar and her small group of initial volunteers had no choice but to be creative and innovative from the start—a skill set she credits RISD for giving her.

“I learned at RISD that design curricula and exposure to creativity and the studio structure all help young people focus on the present moment. We quickly realized that the studio approach created the space for our refugee students to process their trauma,” Attar explains.

To translate her philosophy into a tangible program, the foundation partnered with the Massachusetts based NuVu Innovation School to create a curriculum that blends design, art and technology training free of charge. Attar says the collaborative spirit she found infectious at RISD also laid a powerful foundation for her approach to building her organization in close concert with the community she was determined to help.

“The architecture program at RISD definitely showed me the power of listening and the need to coauthor your designs and your solutions with the community impacted by new architecture—otherwise it won’t actually work in practice,” Attar says. “So many of the failures we see in humanitarian aid efforts can be traced to failing to coauthor a vision and road map with the people on the ground who will be directly impacted.”

Karam House curricula and workshops are tailored in Arabic, and students have access to tools, studio space, woodshops, Wi-Fi, computers, professional mentors, a kitchen and a library, along with space to socialize. Attar explains that spaces become second homes for many of the young people they serve and offer opportunities to socialize in a safe environment they might not otherwise have access to. And, consistent with the organization’s ambition to offer long-term assistance, former students and kids who worked and learned at the Karam Houses are regularly given support after they move on, whether it be helping with their résumés or providing them with references and even portfolios of their work that they can show to prospective employers.

This is all part of a novel idea the organization has embraced, which Attar calls “radical generosity.” “Instead of just sending money through a large international charity, our idea of radical generosity when it comes to refugees is more about the act of giving all of yourself and giving in a way that is not necessarily how people think about charity,” says Attar.

A POTENTIAL PITFALL aid organizations fall into is the well-intentioned tendency to define refugee populations as permanent victims. But Attar says that mentality can have a psychological impact on displaced people who feel limited and unable to rise above that identity as a refugee. Karam teaches the young people who come through its doors to redefine what it means to be a refugee. She recalls her own experience coming to RISD from Syria and the sense of endless potential she felt on campus. That ethos of possessing limitless potential guides the message Attar instills in young refugees.

“At RISD, we learned that if you imagine it, you can build it, you can design it, you can create it,” Attar says. “This is missing from the life of a typical refugee child or youth, and I always believed that if we created this place where they were not defined by their displacement and by what they’ve lost and they’re expected to contribute and create, their personal expectations will rise exponentially.”

While at Karam House, Attar says one of the most noticeable changes can be seen in the rapid improvement in public speaking and presentation skills students display after they’ve had to present a couple of projects. They often come in shy, but after two or three days of studio work, they become self-assured presenters and speakers.

While the students pay no tuition and don’t receive any sort of formal diploma or certificate, the deal is that they are treated with dignity, respect and high expectations are set. In exchange, they’ll have access to educational opportunities and can develop vocational skills, as well as a continued support network. The students know they’re expected to make positive contributions to their communities wherever they end up, whether back in Syria, Turkey, or anywhere else around the world.

“We wanted to flip the concept of humanitarian aid, so instead of giving this sprinkling of help to survive, we give [these young people] the space to flourish and realize their potential, explore their curiosities and interests in a way that allows them to fully contribute to the world,” Attar says.

Images from top to bottom: NurPhoto, gettyimages.ca. Anadolu Agency, gettyimages.ca. SOPA Images, gettyimages.ca

Words by Doug Daniels