The Melt

Acacia Johnson documents the impact of climate change on the Arctic.

IMAGINE THE ARCTIC as a frozen sea surrounded by continents. The United States, Canada, Iceland, Greenland, Norway and Russia all border the Arctic Ocean, where thick, multi-year sea ice has historically formed the foundation of a rich marine ecosystem. Algae growing beneath the ice feeds the zooplankton that support the food chain up to seals, walruses and polar bears, all of which depend on ice for their reproductive success. Arctic Indigenous peoples have relied on these animals for food for millennia and use ice as a platform for travel between communities and to access hunting areas. The ice has also kept the region largely unreachable by ship except during short windows of time in the late summer, contributing to its remoteness.

Today, the Arctic is warming at four times the rate of the rest of the planet, and its sea ice has decreased by two-thirds since it was first measured in 1958. Studies predict that summers could be ice-free as soon as 2035 if greenhouse gas emissions are not radically reduced—contributing to a surging interest in the Arctic by northern hemisphere countries as a path for shipping lanes, natural resource extraction, commercial fishing, tourism and military activity.

In the past decade, marine vessel traffic in the Arctic has more than doubled. Ships will soon be able to bring lucrative commercial opportunities into regions where few have previously existed. While development can economically benefit many of the Arctic’s four million residents—about 10% of whom are Indigenous—it also marks a dramatic shift from the subsistence lifestyles and traditional values of many remote communities.

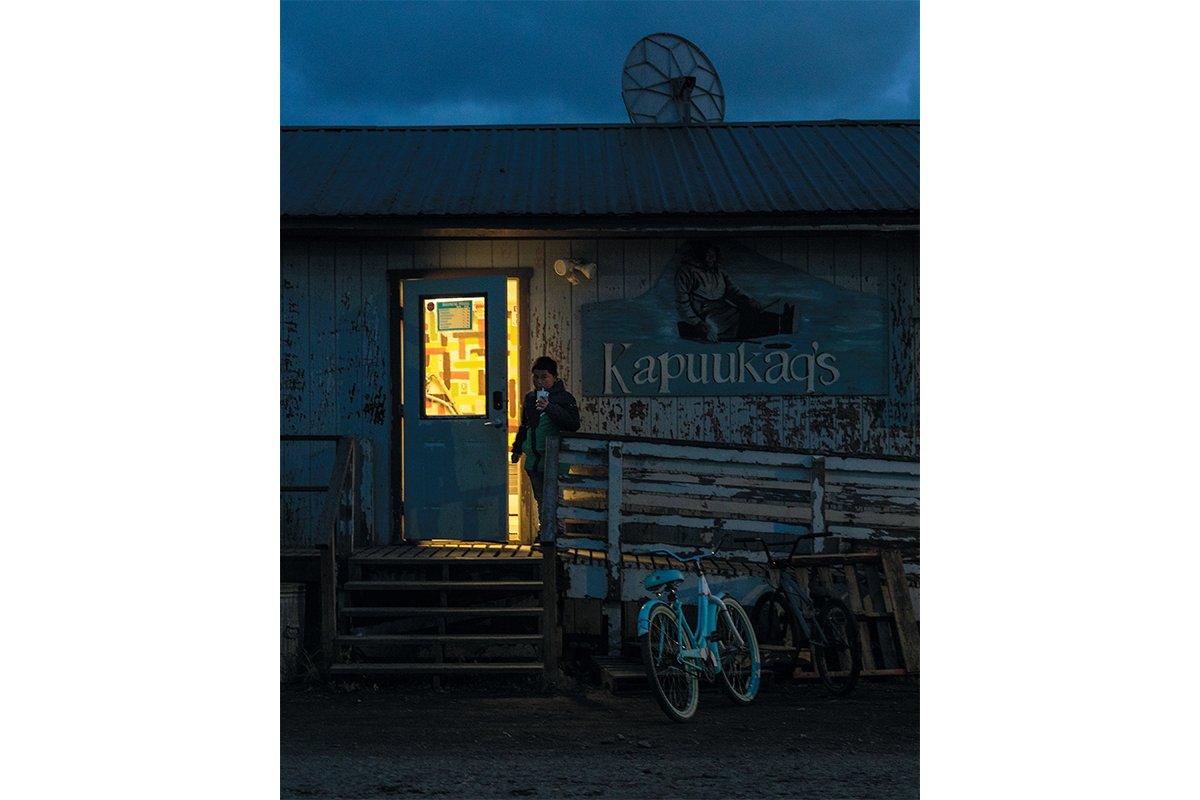

Top image: A boy exits a convenience store in Unalakleet, Alaska, an Alaska Native village of about 760 people on the coast of the Bering Sea. The nearby city of Nome, a hub for Unalakleet and other small villages on the Seward Peninsula, is set to become the first Arctic deepwater port in the United States.

Bottom image: Inupiaq writer Laureli Ivanoff and her son, Henning Nelson, on the windswept shore of Unalakleet, Alaska. Ivanoff explains that climate change is threatening some of her community’s most important subsistence traditions, especially the annual hunt for ugruk (bearded seal). She described a profound sense of loss that her son, already passionate about hunting, may never have the chance to hunt for seal if sea ice continues to disappear.

Climate change has already led to a rise in food insecurity in many parts of the Arctic, as animal migration patterns change and hunting grounds become inaccessible. While an increase in ships can lower prices for imported foods, they also pose additional risks of oil spills, debris, discharge, marine mammal strikes and critical habitat loss through underwater noise pollution and fragmentation of sea ice by icebreakers.

Top image: A tourist ship, in search of polar bears, leaves behind a trail of crushed sea ice off the coast of Spitsbergen, Svalbard. Marine mammals that rely on sonar and acoustic communication are particularly vulnerable to underwater noise pollution and can cease feeding behavior if disturbed.

Bottom image: A sculpture of an Inupiaq hunter, together with the frame of an Umiak (traditional boat), mark the entrance to a private camp near Safety Sound, Alaska. This protected lagoon and migratory bird habitat near Nome has been a hunting, fishing and gathering ground for Alaska Native peoples for millennia.

As human activity in the Arctic increases, the need to adapt is inevitable. Understanding the long-term environmental and social implications of proposed development will be critical in ensuring that changes are made in the genuine interest of those who live there. Essential to this success is the involvement of Arctic peoples in deciding what happens in their homelands—the people who understand the changes already affecting the environment better than anyone else.

Words and photos by Acacia Johnson 14 PH

Header image: A subsistence camp faces the shore of Safety Sound. The lagoon remains an important subsistence area for residents of Nome and surrounding communities, but is under pressure for commercial development. In 2022, a Nevada-based company’s proposal to dredge Safety Sound for gold was denied by the US Army Corps of Engineers.