Shaking the Tree

A community-informed curatorial process brings the life and work of Nancy Elizabeth Prophet into sharp relief at the RISD Museum.

In a glass case in the RISD Museum is the diary of Nancy Elizabeth Prophet, the 20th-century sculptor and Rhode Island native who was one of the first known women of color to graduate from RISD. The entry for March 10, 1929 reads simply “Starvation.” The next entry, from March 29, bears just the phrase “I will not bend an inch.”

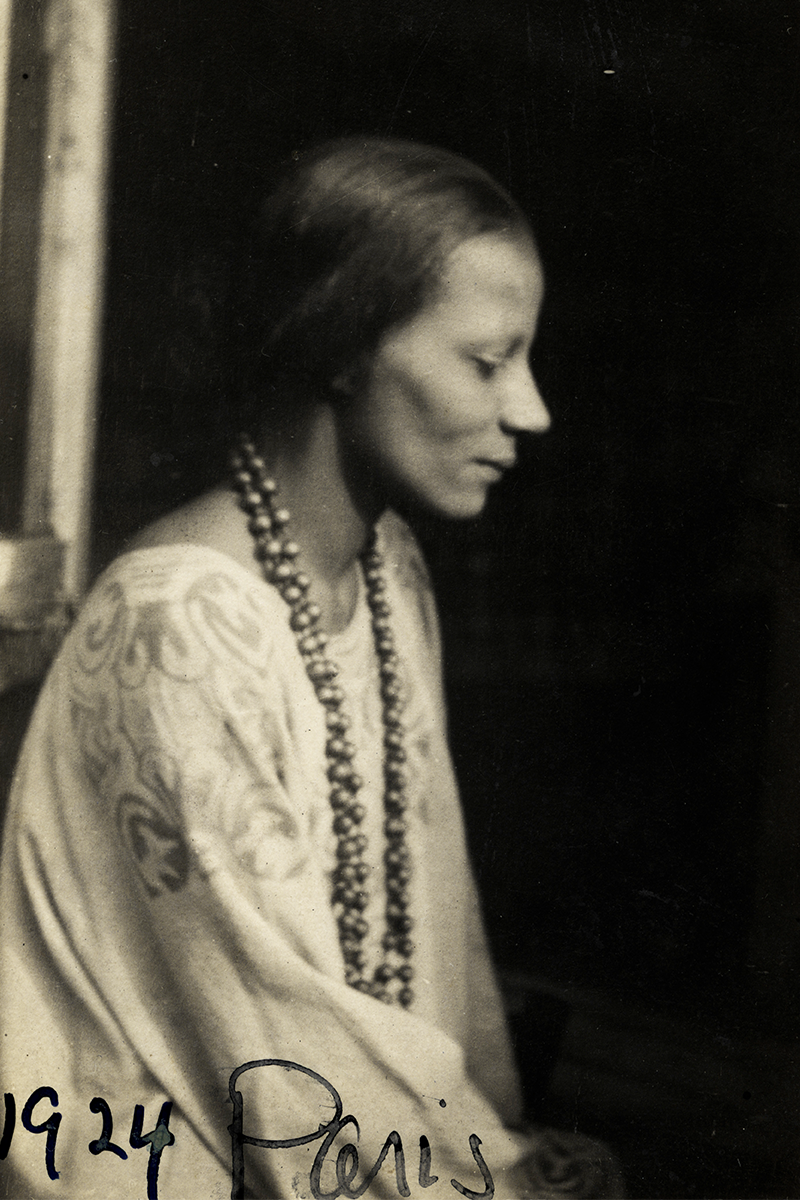

That is the source for the title Nancy Elizabeth Prophet: I Will Not Bend an Inch, an exhibition that opened at the RISD Museum on February 17, 2024 and is on view until August. The exhibition includes marble and wood sculptures, painted wood friezes, watercolors and photographs of archival documents and lost works.

Today, Prophet’s sculptures are widely appreciated for their depth of presence, uniquely straddling European classical traditions and modernist sensibilities. But in 1929, as an expatriate artist living in Paris, she was underrecognized and battling the art world structures that excluded her as a woman of African American and Narragansett heritage. Her importance as an artist, as well as the struggle and formidable spirit her diary entries reveal, have long inspired community members in her home state and elsewhere to delve into her life and work.

Thus, when the RISD Museum began planning an exhibition of Prophet’s work and archive, museum staff invited artists, scholars, neighbors, activists and others whom they knew had explored the artist’s life and work to participate in shaping the show. This consultative curatorial process, refined over years of exhibitions, ensures the museum is accessible, accountable and responsive to the community in which it resides.

“We at the RISD Museum did not take the position that we are the authority on Nancy Elizabeth Prophet just because we hold her work and this is her alma mater,” says Kajette Solomon, the museum’s social equity and inclusion specialist and a co-curator of the exhibition. “Prophet was born in Warwick, interred in Pawtucket and she is well-known and beloved in the state. We invited input and thought partnership with community members who we knew were invested in her legacy, and it grew from there.”

In 2022, Solomon, with co-curators Sarah Ganz Blythe P 22, deputy director of exhibitions, educa tion and programs and Dominic Molon, interim chief curator and Richard Brown Baker Curator of Contemporary Art, held an initial community convening to explore the scope and content of the show. Additional meetings with more participants followed, with community members like Sylvia Ann Soares, who has staged dramatic performances based on Prophet’s diaries; Ray Rickman, executive director of the nonprofit Stages of Freedom; Nancy Whipple Grinnell, curator emerita at the Newport Art Museum; Lorén Spears, executive director of the Tomaquag Museum; professor and historian Mack H. Scott III and others. In addition to yielding new archival material and a new work included in the show, their input and insight, along with that of many others, was essential to creating an exhibition that fully celebrates Prophet’s life and work.

“It was a wonderful, iterative process,” Ganz Blythe says. “Starting with what we knew, we also wanted to learn from the knowledge existing in the community. We presented stages of the project to the group so they could see where all their feedback led us, and encouraged them to invite more people to the conversation.”

Solomon and Ganz Blythe say that bringing in community members early is key to creating a responsive, community-centered museum. Often, Ganz Blythe says, museums ask for input at the end of exhibition planning, when there is not much time to receive impactful feedback or to be responsive to it.

At the RISD Museum, community involvement in curation goes back at least a decade. For a 2014 show called Locally Made, which aimed to reflect Providence’s creative community, curators worked with both RISD graduates and the many area artists who are not alumni. That was a moment, Ganz Blythe recalls, when staff needed to think through what it meant to be more responsive to the creative community, what avenues to pursue and how to reach out beyond the institution.

That set the stage for additional community-centered work leading up to the 2019 debut of Gorham Silver: Designing Brilliance 1850-1970. The exhibition focused on the Gorham Manufacturing Company, a major employer in Rhode Island and a one-time worldwide industry leader in creating silver products. Curators visited community libraries and sites impacted by the company, like Mashapaug Pond, which was contaminated by chemicals discharged from the factory. They gathered stories from residents about what it was like to work at the factory and considered Gorham’s social impact in planning the show. For museum workers, that process “is not about the objects, it’s about a relational way of working,” Ganz Blythe says.

Dialogue with practicing artists, local teachers, student groups and members of the public was also central to a major 2022 reinstallation project. With community input, the museum reimagined 9000 square feet of gallery space dedicated to 20th and 21st century art. The resulting galleries draw connections across perspectives, cultures and media, and allow visitors to experience contemporary and modern art in a global context.

“For us, one thing that was very important to think about was how, when we collect artists’ work, do we actually talk to the artists about how they might imagine their work being shown? For alumni artists, what were their perceptions of the museum when they were students? How does it feel to have their work displayed?” Ganz Blythe says.

With the Prophet exhibition, what the artist wanted, according to her diaries and letters, was top-of-mind for the curators. Prophet never had a solo exhibition during her lifetime, Molon notes, which is something that can signal an artist has “arrived.” And yet, the curators make clear, this solo exhibition is not the final word on Prophet, but a start. Molon says he hopes this exhibit, which will travel to the Brooklyn Museum and the Spelman College Museum of Fine Art in 2025, will “shake the tree” and yield more about Prophet, just as the group effort of all those who helped shape the show added dimension and depth to this artist finally beginning to get her due.