Of the Time

In just five short years, these alumni have long lists of accomplishments.

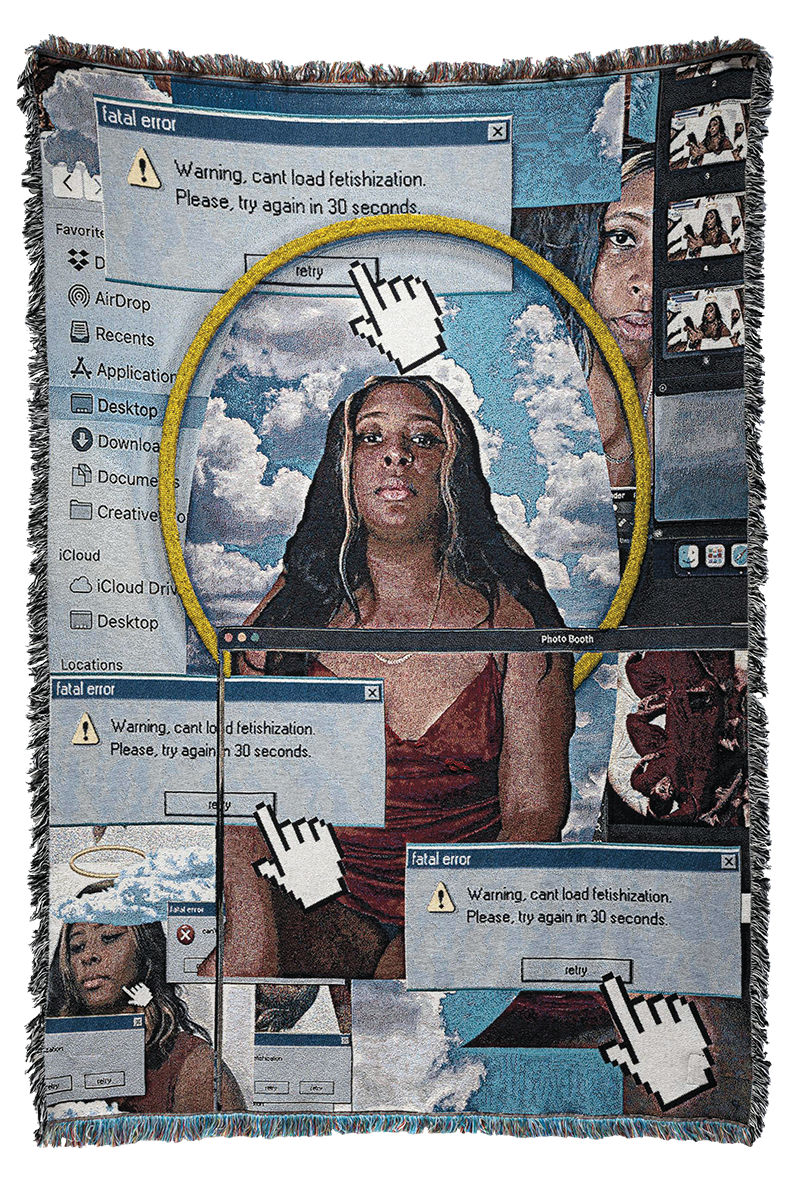

Qualeasha Wood 19 PR

Who gets the right to be audacious? Is it textile artist Qualeasha Wood, a Black daughter of military vets from the Jersey Shore? Is she audacious when she weaves self-portraiture, religious iconography and digital motifs onto large tapestries, a medium almost solely reserved to tell the tales of white men, or is she just being narcissistic? “I’m challenging who gets to control the narrative of audacity as something that is risk-taking and bold. A lot of my white peers get the grace; I was asked how dare I insert myself so directly into the canon,” says Wood.

She didn’t set out to disrupt the status quo. In fact, as an artistic kid who used to draw portraits on wood panels in ballpoint pen in a town she describes as “pinnacle gentrification,” she often felt like she existed in two worlds and just wanted to fit in somewhere. She couldn’t imagine a place in her parents’ military world, so she applied to art school. RISD, with a less than 10% Black student population, didn’t prove to be an ideal fit either, at first. “I felt isolated. I was trying to make the work and fix the environment so that I could get all the benefits that I was promised when attending a top art institution,” she says. It was in the fixing that she began to realize that perhaps it was better to stand out than to fit in. “I told myself that I was going to make it count. I couldn’t afford to be closed off, I couldn’t afford not to stand out. I taught myself over time to fight for what I deserved and to not allow myself to be made small,” she says.

Wood ditched illustration. “I realized I didn’t want to be a perfect draftsman. I wanted to do something that was fine art and loose,” she says. A phrase came into her head and took roots; “God is young, hot, Ebony, and she’s on the internet.” A phrase born from feeling othered that Wood felt needed to be heard. She silkscreened it, letterpressed it, etched it, printed it and tried to make it work as a photograph. It wasn’t until Wood saw a photo blanket at her grandmother’s house that she realized an image could be woven.

Working in Jacquard weaving was scary at first. “But that’s what made it feel worth doing,” she says. “I always felt like the work wouldn’t be taken seriously until it was woven. I don’t want it to be a fantasy, I want it to be real. Jacquard wovens make the work competitive,” she continues.

Wood was exhibiting her tapestries before she graduated from RISD and signed with her gallery, Kendra Jayne Patrick, soon after. Her work is in the permanent collection at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York and the Museum of Fine Arts in Houston. She’s exhibited at Art Basel as well as multiple shows around the world and has been featured in The New York Times, The New Yorker, Essence magazine, Harper’s Bazaar and W magazine, just to name a few.

Self-portrait photo by the artist

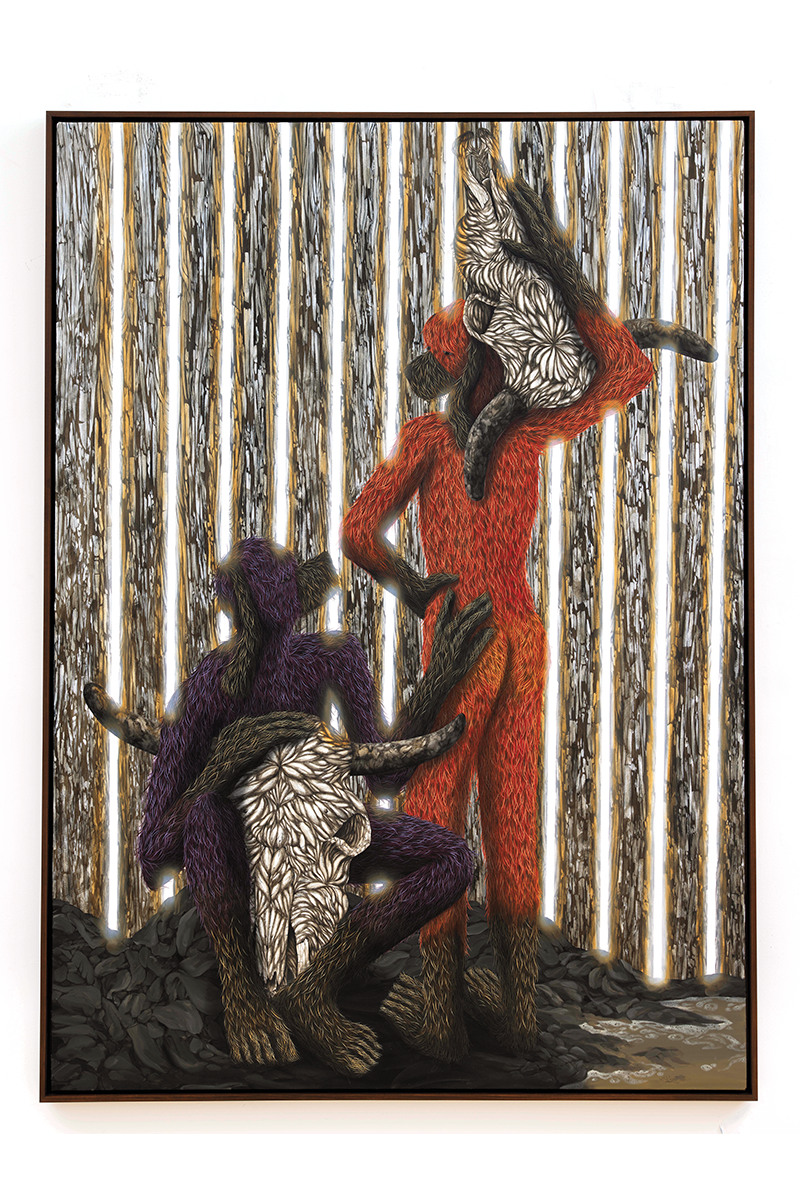

Drew Dodge 22 PT

Drew Dodge’s mischievous paintings depict figures that are part human, part beast and part cuddly cartoon, often set against a Southwestern backdrop. There is humor to them, as well as darkness. They are playful, sexual, fantastical and real. The inherent duality in them also resides within their creator. Dodge talks in a soft-spoken, slow cadence, but never for one second are you to believe he is bashful.

Dodge came to RISD via Arizona. A creative soul, he had illustrated, sculpted and done video work but had never painted before art school. “I was drawn to the Painting department because it was really open. Painting didn’t have to be defined as oil on canvas, and at the time I wanted to do textiles, sculpture, drawing, video art,” he says. He took full advantage of the tolerance and experimented.

It wasn’t until his junior year that he decided to focus. “The summer before my junior year, I started to think about what I wanted to do once I got back to school. I wanted to take all of my ideas and keep them in a flat rectangle. I wanted to represent my ideas uniformly and cohesively,” says Dodge. It was in the narrowing that he found his colossal voice, spoken through the unique figure that routinely appears in his work. This creature had never before been imagined by Dodge. “Before I started painting, my work was more critical. I was interested in the American landscape, consumerism, production, structures and rules, and how sexuality fits into all that. Once I turned to painting, I became more sensitive and the work became more personal. I started telling my narrative through the figure,”he says.

As he showed his story through a fantastical creature on canvas in large, dense oil paintings, he took to Instagram to represent himself. Jonathan Hoyt, the partner and director of the Steve Turner gallery saw Dodge’s work and reached out. After a phone call, the gallery was ready to sign. “They could sense that I was serious and ready to work on a solo show,” says Dodge. A similar situation happened with the 1969 Gallery, which signed Dodge after one meeting.

Since graduation, he spent a little over a year in a residency with the Silver Arts Project and he now has a piece in the collection at Miami’s Institute of Contemporary Art. He has many more shows planned including one with the Semiose gallery in Paris, and another at the Untitled Art Fair, in Miami.

Photo of the artist by Daniel Rampulla

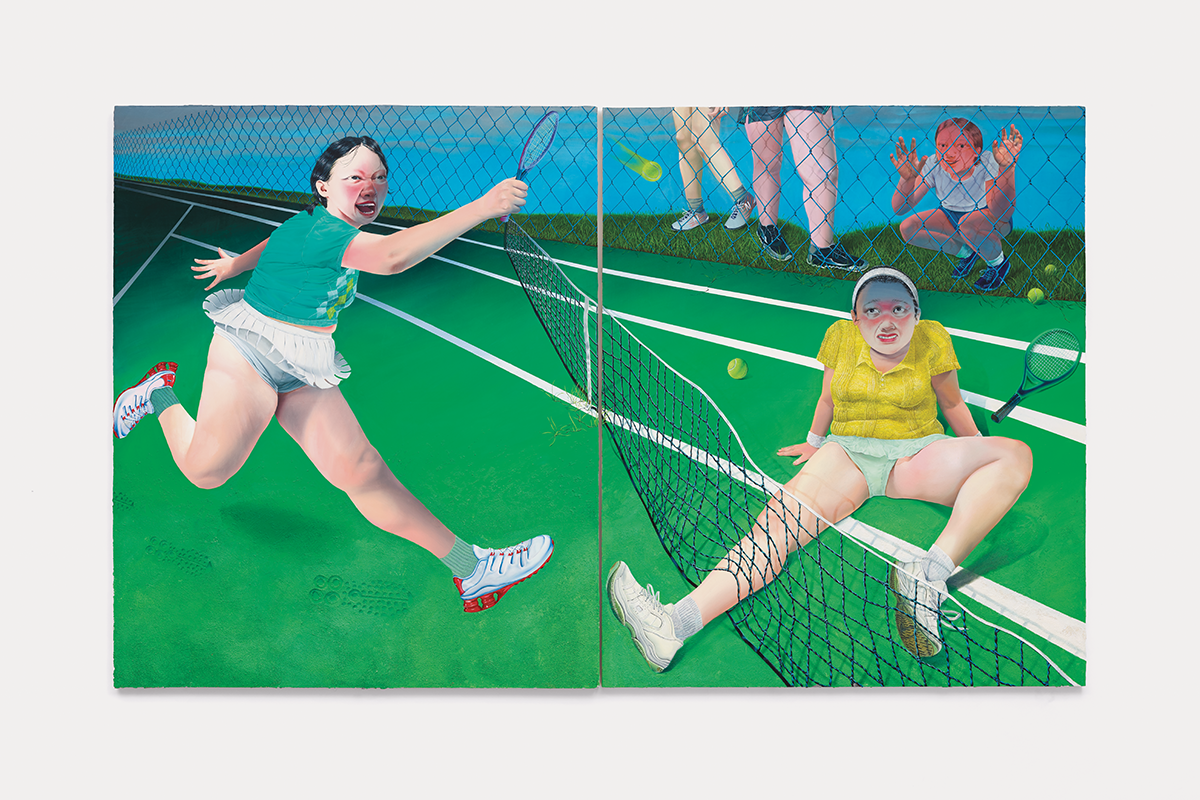

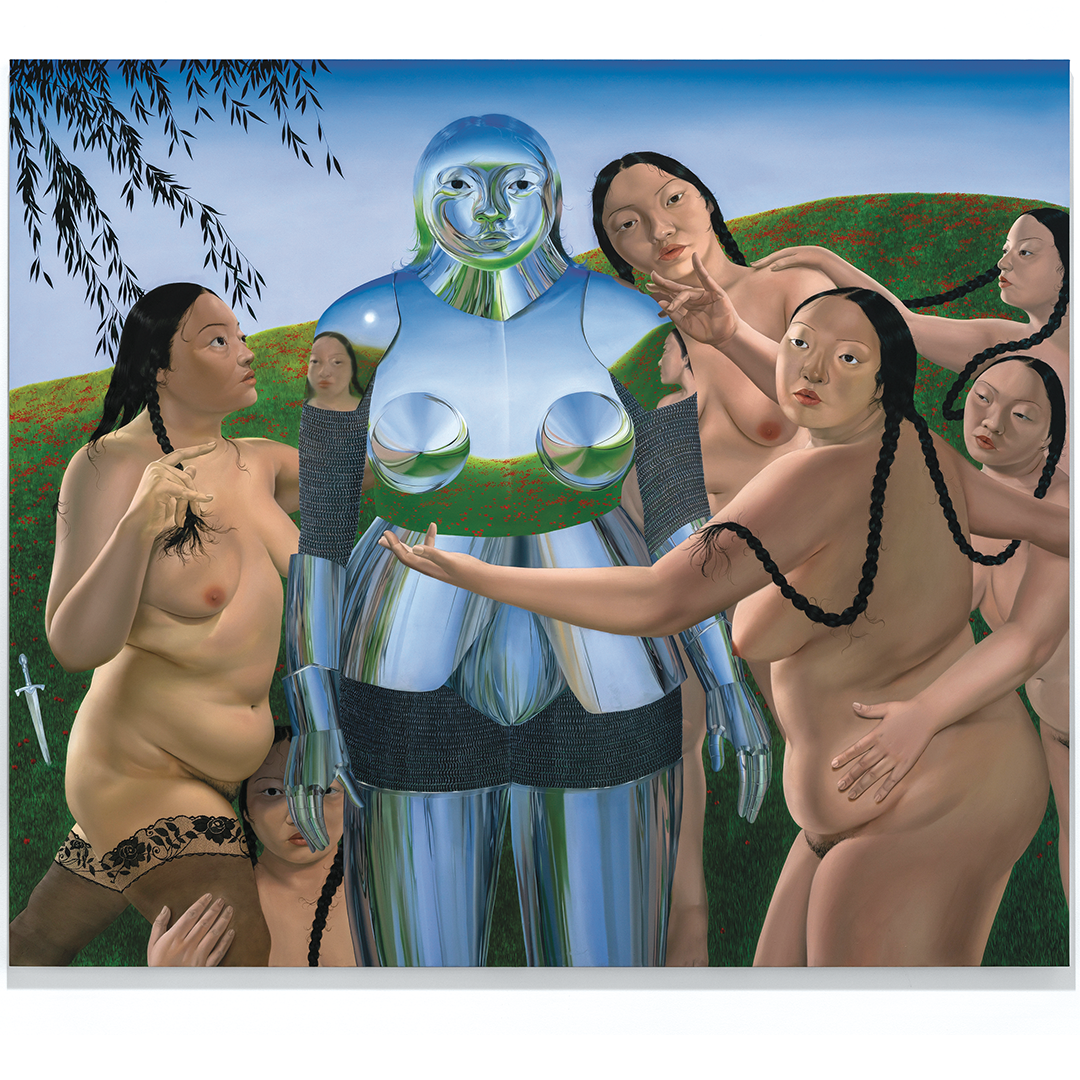

Sasha Gordon 20 PT

When Sasha Gordon talks about her paintings, they seem to be made not of oil and canvas but of memories, sweat, tears and laughter. “All of the paintings I make take the life out of me. I’m very immersed in them,” she says. And to her they aren’t just materials waiting to be manipulated; they’re an outlet for her to examine past trauma, a mirror to hold up to herself and the world, a teacher that hones her craft, and a studio partner. “Painting is an isolating practice,” says Gordon: alone time with just her canvases, to which, once complete, she says a sad farewell. “It’s like I’m giving away my babies or my limbs," she says.

As her career has progressed, the goodbye has gotten easier. Gordon feels fortunate that some of her pieces are now in museums (Hammer Museum, Miami Institute of Contemporary Art, Los Angeles County Museum of Art and Houston Museum of Fine Arts) that she can visit. And her practice has evolved into one that is a bit freer, a bit looser, so she doesn’t hold on so tightly.

When she first arrived at RISD she was “reflecting a lot about my past experiences. I was learning about myself and feeling more whole as a person. I started painting a lot about identity and how I fit in certain spaces. Sometimes I would spend an entire semester on one or two paintings because I was so obsessive with detail and making things realistic. My professors were always pushing me to be looser,” Gordon says. It wasn’t until she went to Rome with the European Honors Program her junior year that she was able to pick up her head and look around. “I was with only twenty other students and I was able to not worry so much about how my art was perceived. I let go. I let parts of the painting breathe,” she says.

She returned to RISD and began to collage together this new style with her old one. “I was attentive to detail but in a different way. There was more variation. I paid more attention to textures and gestures,” she says. She also began to realize that a hyper-realistic painting is “really fast to read because everything is right in front of you. It can be interesting but not interactive. I want my paintings to read slowly, and in order to do that, things have to be told in a different way,” she says.

Gordon’s unique style caught the attention of art collector Jonathan Travis, who connected her to Matthew Brown, her current gallery. She started showing in her senior year and hasn’t stopped since. She’s also been featured in numerous publications, including Vogue, and attended the Met Gala and this past December, her solo show Surrogate Self opened at the Institute of Contemporary Art in Miami. There was a line down the block to get inside.

Photo of the artist by William Jess Laird

Sahara Clemons 23 AP

Sahara Clemons has been sewing since she was seven. She “appreciates both the technical and the conceptual aspects” of apparel design. “How do you reach your audience, how do you fit a garment, how do you create a concept that feels relatable but also marketable?” she asks. These challenges within the medium spark her creativity. “There’s always a necessary challenge with your craft that makes you keep pursuing it,” says Clemons.

If challenges keep her creating, then it was no surprise that Clemons was chosen as the one senior to represent RISD in the Supima Design Competition last year. Launched in 2008, the competition introduces the next generation of designers to the fashion industry with a New York Fashion Week runway show judged by a prestigious panel from fashion and media. The winner not only gets bragging rights and invaluable exposure, but a $10,000 cash prize.

Clemons was tasked with creating a five-look evening wear collection in three months using five different Supima fabrics (denim, velvet, cotton, twill jersey and shirting), one fabric per look. The limits emboldened her to rise. “The restraints allowed me to get more creative with the textures and ultimately how the designs came to be,” she says.

Her collection, called Skin Deep, was inspired by her battle with eczema. “I had a really hard time growing into adulthood, my feminization and sensuality as a woman, especially when it came to building relationships and developing a sense of intimacy. The collection speaks to that desire for connection and the fear to do so because of your relationship with your body. Each of the looks represents a meta-morphosis, a healing journey. The first is covered up and conservative, while the last look mimics cysts and bumps, and the beauty in that,” she says.

Although she didn’t win, Clemons certainly didn’t lose. After the competition, one of her looks was showcased during Paris Fashion Week for the Supima Design Lab, which features both emerging and established designers from around the world. Clemons wore an outfit she designed, thereby actually presenting two looks to the esteemed guests. These opportunities she does not take lightly. “It’s so difficult in this industry to get the opportunity to create your own body of work. I’m proud of what I made. And I’m feeling optimistic about how all of this will be a stepping stone for future endeavors,” she says.

Her next step is a move to Los Angeles, and then eventually she hopes to land in New York City. “I want to start my own ready-to-wear brand. But right now I’m taking the steps to build those resources in order to do that,” says Clemons. Rest assured, any hurdles she faces will only make her jump that much higher.

Photo of the artist, courtesy of Supima

Zoë Pulley MFA 23 GD

In many ways Zoë Pulley’s journey started at the end. She held a BFA in fashion design from Virginia Commonwealth University and was working in activewear in New York City. “But everything I was doing outside of work aligned with what is now my practice. I had a jewelry line called Grand Sands, named after my grandma, and I was bookmaking to tell stories through various materials, mostly textiles. I hit a point where my day job wasn’t serving me and I wondered what was next,” she says.

She turned to her father for advice. “He always steers the ship,” she says. But unlike many parents, he wasn’t steering toward a stable job. A writer and journalist, he didn’t push Pulley to security but toward her heart. “I’ve been very fortunate, especially as a Black maker, to have parents who have been so supportive and pushed me to really hone the skills I naturally have,” she says. Her father encouraged Pulley to go back to school for her MFA. She applied and was accepted to multiple programs but RISD offered her the Society of Presidential Fellowship.

Once she was a student again, she decided to major in graphic design, again with encouragement from her father. “A lot of the visual narratives I created incorporated typography. My father saw graphic design for me as a conceptual means to an art practice,” she says. Luckily, it was also a major that easily translates into a job: she was hired as a designer at Wolff Olins right out of school after winning the Graduate Graphic Designer to Watch award from GDUSA. But after working full-time for only a couple of months, Pulley learned she had been accepted as an artist in residence for one year at the Studio Museum in Harlem. She didn’t need her father’s advice this time. She left the stable job in favor of art.

The Studio Museum residency culminates in a show that will be hosted at MoMA PS1 as the Studio Museum undergoes renovations. Although Pulley hesitates to get specific about what she’s working on, she says that her interest in textiles and telling stories persists. “I always find myself going back to fabric. A lot of women in my family have sewn, and I have a natural inclination toward it,” she says. Her grandmother often comes up in her work. “Me and her have a lot of parallels. She studied fashion design and is very much a maker’s maker. We work in a similar way and I’ve always been able to talk to her; she just gets it. Plus, she’s lived an incredible life and I’ve learned so much from her. I need to honor this person and give them their flowers while they’re still here,” she says.

Photo of the artist by Nik Muka

Words by Abby Bielagus. Lead image Sasha Gordon, Sore Loser, 2021. Photo by Ed Mumford.