Odyssey in the Andes

A RISD professor, a Hyundai lab and a group of Argentine artisans turn robotics upside down.

High up in the Andes, near the Argentina-Chile border, a caravan of horses and mules laden with riders and equipment picks its painstaking way across a rugged mountain range under a deep-blue sky and a blazing sun. Leading the sprawling pack is another creature, neither human nor equine. With metal legs and a torso, neck and head fashioned from bamboo, this unlikely adventurer—which looks a lot like a llama—is Guanaquerx, the first robot to cross the Andes mountains.

Both a robotic art project and a multiday performance-expedition, Guanaquerx was envisioned by interdisciplinary artist and RISD professor Paula Gaetano Adi to reimagine the Argentine general José de San Martín’s epic 1817 crossing of the Andes to liberate South America from colonial rule. Gaetano Adi worked on the project, which culminated in Guanaquerx’s triumphant arrival at the Chilean border on January 24, 2024, with Hyundai’s New Horizons Studio, which has offices in Fremont, California, and Bozeman, Montana, and a team of local artisans and engineers in Argentina.

Gaetano Adi, who grew up in San Juan, in western Argentina, has been working in robotics for the past decade. Most recently she has been investigating the possibilities of combining what she calls an “alternative cosmotechnics,” with artisanal crafts on the one hand and robotics technology on the other.

In 2022, Gaetano Adi taught a studio class called Robotics for the Pluriverse as part of the RISD x Hyundai Motor Group Research Collaborative, a multiyear partnership exploring the relationship between nature, art and design. Gaetano Adi and her students held frequent Zoom meetings with Hyundai designers and engineers, and that’s where she met John Suh, head of New Horizons Studio, a unit within the Hyundai Motor Group’s US R&D Center focused on developing off-road autonomous robots.

When Suh, who launched New Horizons four years ago, showed Gaetano Adi sketches of his team’s Ultimate Mobility Vehicle, which is designed to tra-verse difficult terrain, she saw an opportunity. “I was like, ‘Do you have a place where you can test this?’ And he was like, ‘No, we’re in the development stage.’ So, I said, ‘Oh, I think I have a place where you can test this.’ I told him about Guanaquerx, which was really just an idea at that time. And he said, ‘Well, let’s do it!’”

Gaetano Adi was inspired by the guanaqueras—makeshift all-terrain vehicles developed by amateur car mechanics that could navigate parts of the Andes previously only accessible by horse or mule—of her hometown. “I was looking at how they approached the making of those vehicles with the scarce resources that they had,” she says. “I showed John and told him that I wanted to make something like that as an autonomous machine. His studio was developing unmanned vehicles, so it seemed perfectly aligned.”

For Suh, the project was appealing partly because it would serve as an important proof of concept for his fledgling vehicle prototype. “It was obviously a very remote location with all kinds of different types of terrain,” he says, “so technically, that alone would’ve been enough. But on top of that, what excited me was that Paula was trying to create a different kind of art project, one without walls, moving in the world.”

If you’re asking at this point why Gaetano Adi wanted to cross the Andes with a robot, that’s a fair question. Part of it, she says, was about trying to disrupt the way we think about robots. “Any science fiction narrative with robots always ends in an apoc-alyptic scenario with robots becoming aware that they’re enslaved forced labor and then rebelling and killing their masters to achieve emancipation,” says Gaetano Adi. “I’ve been thinking about other ways we can imagine a technological revolution.”

The Guanaquerx project, she says, was a way of using robotics not to claim a great technological achievement for space exploration or as another colonial operation to conquer worlds but instead to reimagine San Martín’s liberatory crossing of the Andes mountains.

“Growing up we knew about this major event that had happened here 200 years ago that consolidated the freedom of South America from the Spanish,” says Gaetano Adi. “San Martín’s plan was to cross the Andes in the most unexpected and difficult place, surprise the Spaniards and liberate Chile, and then to set sail and surprise the viceroyalty of Peru from the ocean. To execute the plan, he first needed to cross the Andes, which was an almost impossible task. My project was a way of reenacting this gigantic unexpected endeavor with another radical odyssey. I knew that a robot couldn’t theoretically make the crossing, but I also knew that with the help of all of us as a collective ‘army,’ we could help this robot become liberated in a completely different sense—not going after and destroying humanity but showing that technologies can be produced and thought of in a different way, for humans and with humans.”

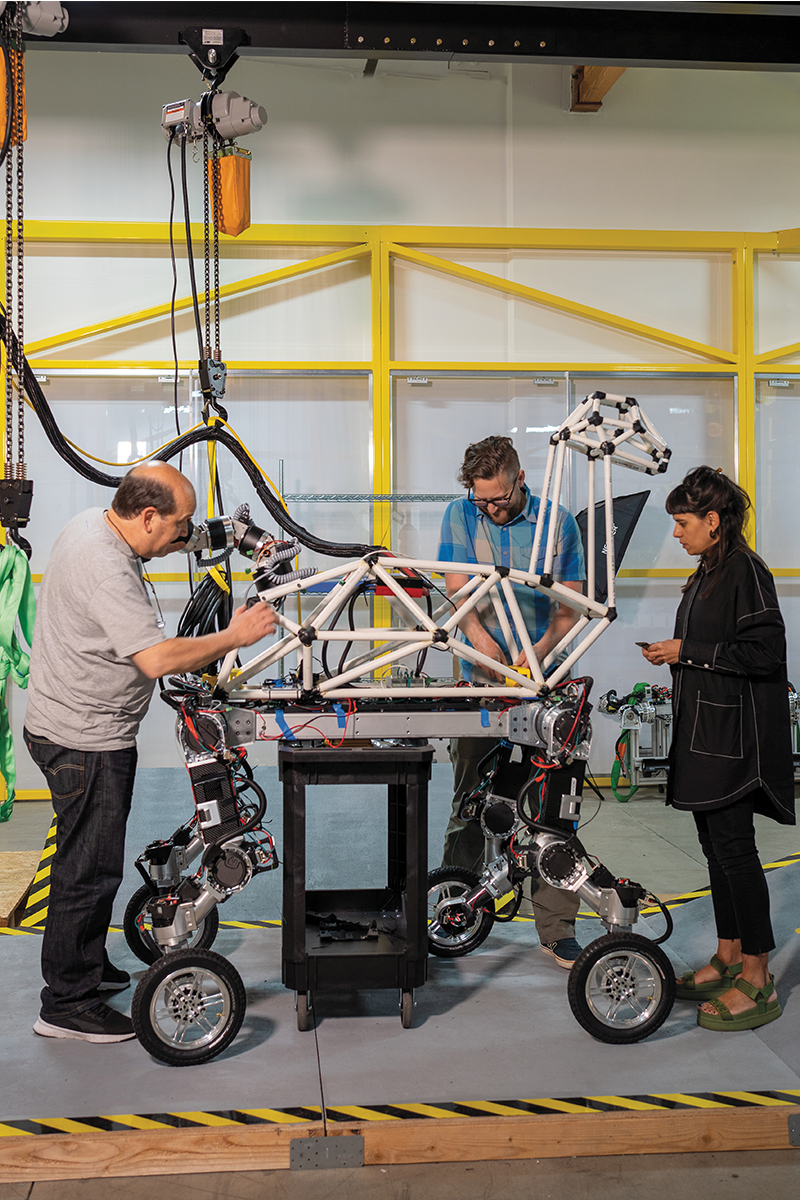

To get a clearer sense of whether the Guanaquerx project was even feasible, in early 2023 Gaetano Adi arranged a scouting trip with New Horizons mechan-ical design lead John Strong and several baqueanos (local guides) to trace the route across the Andes. “That was a crucial piece because that’s when they understood what they were up against and how vast the Andes are,” says Gaetano Adi. Up until then, says Strong, the project had felt very nebulous. “The scouting expedition not only made it real for me,” he says, “but it also put it on the radar of the whole engineering team.”

At an early stage, it had been suggested to Gaetano Adi that she could use an existing R&D prototype and turn that into the Guanaquerx. She resisted that idea and, in what felt like a huge leap of faith but also “a magical moment,” insisted that it was crucial the robot be made from scratch.

Ijlal Muzaffar, a professor of the theory and history of art and design at RISD who followed the project from the beginning and participated in the expedition, found this decision intriguing. “If they had simply bought an expensive remote-control vehicle and put the Guanaquerx on top of it and crossed the Andes with that, it would’ve validated our belief that through technology we can control anything. Instead, everyone had to reinvent the wheel completely, which meant they came in with a sense of responsibility, an investment to make this thing happen.”

For more than a year, Suh had a team of at least seven engineers working on the project in Silicon Valley, while Gaetano Adi worked with her own team of artisans and engineers in Argentina and periodically visited the California lab. Everything about the vehicle was “a giant experiment,” says Suh. “We had to make it resistant to dust and waterproof and be able to control it and have it handle the terrain. It was an amazing collaboration, where we essentially built the lower part of the vehicle that could move on the ground and then jointly figured out the mechanical and electrical connections to put a body on top with its own tail and its own unique design.”

The idea of making the robot resemble a guanaco—a camelid native to South America—came to Gaetano Adi early on, inspired by the local lore of the Yastay, the mythological guanaco protector of Andes ecology. “We didn’t want a reincarnation of San Martín,” she says. “It had to be something else, and the guanaco is a very special animal in this region and is one of the only mammals that can live at such high altitudes.”

As the January 2024 departure date for the expe-dition drew near, members of the team converged on the small town of Barreal, Argentina, about two hours from the base of the Andes.

For Miguel Lastra, project manager in RISD’s Office of Strategic Partnerships, which supported the project from the outset and served as the main liaison with Hyundai Motor Group, the trip was powerful. What struck Lastra most in the days leading up to the trek was the sense of community Gaetano Adi had built among the various collaborators. At a celebratory dinner held for the entire group on the first night, he remembers a feast not just of traditional Argentinian food but also of fellowship.

“Here we are sitting at a table and having this conversation where the engineers are able to talk to the videographer,” he recalls. “The sound designer is talking to the guy who built the frame of the robot out of bamboo. I’m sitting across from a philosopher, Paula’s research assistant, and beside one of her engineers who had worked on the robotic tail. Even her family was roaming around here and celebrating with her.”

A pre-trek procession through the streets of Barreal brought out crowds of townspeople who waved specially designed Guanaquerx flags as they witnessed a parade like no other, with the robot leading the way, followed by a retinue of mules and horses and people.

The whole town, says Gaetano Adi “was mobilized around this crazy idea.” In that sense, she notes, it aligned with San Martín’s original crossing of the Andes. Lacking support from the national government, the trek was funded and developed by the local people. Fifty percent of the army were African slaves and the other half were local mestizos or Indigenous people, who San Martín sought out and consulted with because they were the people who knew how to traverse the land. In a way, she says, her expedition was a way to reassert the idea of freedom, “the idea of what it will look like if technologies help humanity to truly become free of oppression.”

On the previous year’s scouting trip, Gaetano Adi and Strong had encountered rain, hail and snow, but as the group set off from basecamp on January 18, the sun shone and the air was warm. Though the weather was in their favor, crossing the Andes would still be a challenge, with 4,500-meter peaks, harsh deserts and swift-running streams—a hurdle that called for both manpower and horsepower.

Thirty people made the trip, including engineers, guides, a doctor, a cook and several horse minders and muleteers. The four-legged component included 58 horses and mules, most of which carried equipment, tents and members of the team. Two of the mules, Don Carozo and La Tortuga, were designated to carry Guanaquerx when the terrain got too rugged or impossible to navigate on robotic legs.

That the robot should ride on a mule when the going got tough held its own symbolism. Both Guanaquerx, a mix of robotics and indigenous technologies, and the mule, the offspring of a horse and a donkey, are hybrid creatures. The mule has also throughout history been an enslaved creature used specifically for its labor and crucial to any exploration of new territories.

“There’s some weird kinship there,” says Gaetano Adi. “And maybe Guanaquerx is showing the mule a possibility for emancipation as well. If we eventually have robots that can do this journey, the mules will not be needed.”

No amount of abstract planning or virtual modeling can prepare for what happens in the field, and during the seven days of the trek, Guanaquerx fully morphed from theoretical concept to tangible, and often extremely needy, travel companion. “There was always that extra rock that could make the wheel puncture,” says Muzaffar, who was fascinated by the way the robot began to reveal its “secrets” and limits, whether that was the tail misbehaving because of windy conditions, an actuator unexpectedly breaking, a wheel not tracking properly, the entire robot toppling over or tires popping as they ran over thornbushes.

“The robot kept asking us to help it,” Muzaffar says. “It was like a child in a new environment, learning how to walk, and we were teaching it. Instead of technology giving us more power, we became emotionally invested caretakers. Later, when the engineers and baqueanos talked about the robot successfully walking, they were all in tears. Fixing a nut or tire or tail meant something so much more. I’ve never seen people interact with technology in this way. It really flipped the equation.”

Those daily exercises of troubleshooting and caretaking are what have stayed with Gaetano Adi, too, rather than the “big story” behind what they achieved. She remembers one moment in particular: “We were very, very high in altitude and the robot was not able to do it. He was just not feeling it. Everyone was exhausted because you can barely breathe there, and I started pushing the creature. Everyone was saying, ‘Paula, you’re going to faint because it’s too high. You’re pushing too hard.’ And none of that occurred to me. I was just so into making it work, and it was like that for everyone.”

Reaching the Argentina-Chile border, says Gaetano Adi, was profoundly impactful, so much so that she finds it difficult to describe. “I don’t think words can do anything here, and even images or video cannot fully describe it. You’re just such a little thing in this enormous landscape.”

The trip as a whole was documented extensively with photos, video, social media posts and an interactive website designed by RISD-Brown dual- degree alums Phil Bayer 19 ID and Tiger Dingsun 20 GD. Since internet access was mostly nonexistent during the mountain crossing, much of the website content, which included historical context, philosoph-ical writings and background on the culture and geography of the Andes, was preloaded. A more experiential part of the website allowed viewers to travel virtually across the peaks and ravines and swoop in on key points in the journey.

Guanaquerx itself was also taking photographs and capturing audio recordings. A nighttime camera enabled it to take images of the night sky, and a 3D-printed weather station, created by a team of rural high schoolers in Gaetano Adi’s hometown of San Juan and strapped to the robot’s back, collected information on humidity, wind speed and other climate-oriented data.

On a more performative note, as the expedition made its way along the route, Guanaquerx emitted bleating sounds similar to those of a guanaco and also sporadically beat a chayera drum with its tail and waved the flag of its own revolutionary army of artists, engineers and baqueanos.

Now back in Providence and reflecting on the trip—which she says will take a while to fully process—Gaetano Adi remains moved by the way engineers and guides alike cared for Guanaquerx’s safety and tended to its needs. When it came time to leave the robot in Argentina (it will soon be returned to the US for exhibitions), the engineers, she says, felt like they were leaving their child. Gaetano Adi’s own son, who is three, still misses Guanaquerx and asks, “What is he doing now? He’s by himself. When are we going to pick him up?”

Ultimately, she is not surprised at this level of emotional involvement. “When you work with robotics, you establish such a close relationship with the machine,” she says. “I don’t think it happens with any other object, and that’s the power of this technology. That’s why I work with robotics. Anyone can relate to it. You can be a two-year-old or an 85-year-old, you still develop some kind of relationship with this artificially living being.”

Beyond that, says Gaetano Adi, “we assign personality, we assign behaviors, we assign emotion,” to robots. “And in that projection is where artists working with robotics have a crucial role. We not only can shape the human-machine interaction through its design and intended purpose, but most importantly, we can establish the intelligence or rational and ethical accountability of the artifact itself. That’s a huge responsibility.”

Photos: Pavel Romaniko

Words: Judy Hill