The Long Game

RISD grads with decades of experience share the lessons that stay with them and what keeps them going.

Commitment and drive: two qualities that unite bring to crits, but in the way they dive headfirst into debates, push creative boundaries or carry massive maquettes or portfolios up College Hill without a second thought. For many, the drive to make began in childhood, blossomed fully during their time at RISD and has since become a lifelong pursuit— transcending age and circumstance.

The alumni profiled here exemplitized their studio time or taken plunges into things entirely new. Their drive comes from an innate curiosity and desire to create as well as from lessons learned from RISD classmates and faculty.

Seventy-four years after her graduation from RISD, Joan Gitlow 51 PT has a message for current students, young alumni and anyone committed to art making: "Don't stop doing what you do"

JOAN GITLOW 51 PT SAYS GOOD TEACHING IS TIMELESS.

Some things are firmly rooted in a time and place. Joan Gitlow 51 PT counts her art practice among those things. A painter and printmaker, she says her work reflects her RISD era. Her student years, at the dawn of Franz Kline, Robert Motherwell and Helen Frankenthaler, gave her a starting point for develop- ing a deep understanding of what happens when you organize colors and shapes on a flat surface. She’s been an active member of Cove Gallery on Cape Cod for over 30 years. In summer 2024, at age 97, Gitlow was part of a three-woman show there, featuring her prints and collages alongside sculptures by Silvina Mizrahi and paintings by Ginny Zanger. Gitlow says she is drawn to printmaking for its elements of surprise and discovery. Still, she muses that her art might look “old-timey” to current students. But she says that her approach to art education, with its emphasis on process, is as relevant as ever.

Gitlow taught art for more than 40 years at ele- mentary schools, high schools and universities. It was an experience that allowed her to “witness small miracles of discovery every day.” Inspired by her own classroom experiences and her lifelong passion for drawing, Gitlow developed an online figure drawing manual for teachers that included exercises and examples of student work.

“I believe that drawing is visual thinking in its most direct form, the artist’s primary language,” she says. “I’ve been drawing the human figure since art school and will never tire of it.”

Students of all ages, she reports, were surprised by the progress they could make by focusing their attention on drawing the figure. Watching their growth as artists was incredibly rewarding. It was an experience she had again as she saw her daughter, Kate Gitlow Bramante, and granddaughter, Niki Bramante, experiment, build, explore and develop as artists in their own right.

Gitlow’s love for teaching and appreciation for exploration goes back to her RISD days and the lessons that have stayed with her ever since.

“I could never have become the educator I was and the artist I am if not for the legendary teachers I had at RISD,” she says. “Life drawing with John Frazier stripped away habits, artifice, guesswork. His complex yet blazingly clear instructions and crits taught us to see, build skills, analyze and own our individual imagery and ideas. I taught life drawing to adults and high school kids honed from all I learned from him. Painting with Gordon Peers, Frazier and Bob Hamilton drove us nuts, making us finally ‘get’ Cezanne. It proved to be a gateway to all ideas that came after.”

“RISD meant everything to me and still does,” she says.

Words by Lauren Rebecca Thacker

STAN MACK 58 IL MADE A LOT OF PEOPLE NERVOUS

By age 12, Stan Mack 58 IL was taking Saturday morning life drawing classes at RISD. With other kids, he would draw local high school football players or cheerleaders that were brought in, as he says, “to run around in front of the class.”

Capturing action as it unfolded turned out to be good training for Mack, who went on to pioneer a form of documentary comics that rendered life in New York City in all its fullness and strangeness for The Village Voice. For 21 years, Mack traversed the city, drawing New Yorkers’ interactions at a Bloomingdale’s counter, a squatters’ encampment, a ConEd stockholders meeting or Plato’s Retreat, a swingers’ club complete with a swimming pool. Mack occasionally got kicked out of venues after his sketching, albeit discreet, made people nervous. They thought he was an IRS agent or private investigator. His incredible weekly output for the paper is collected in the anthology Stan Mack’s Real Life Funnies: The Collected Conceits, Delusions, and Hijinks of New Yorkers from 1974 to 1995, published by Fantagraphics last summer.

Mack was inspired by the spontaneity of Providence-based journalist-cartoonists Frank Lanning and Paul Loring, and by the New Journalism of the 1960s, a style that pushed the boundaries of traditional reporting by bringing in techniques associated with fiction writing. Those approaches reshaped traditional publishing, but Mack says studying at RISD had prepared him for it.

“RISD had said, ‘Stay open. It’s okay. You can deal with this. You don’t have to be limited by the stuff that we thought was going to be happening back a few years earlier.’”

Over his long career, Mack has been many things, including art director of The New York Times Sunday Magazine, a close observer of the advertising world with “Stan Mack’s Out-takes” for Adweek, a children’s book illustrator and the force behind graphic and narrative books. Among others, he published a history of the American Revolution, a history of the Jewish people and Janet and Me: An Illustrated Story of Love and Loss, a memoir of his colorful relationship with his longtime partner Janet Bode, and the way they as a couple confronted her terminal breast cancer.

Mack is busy giving book talks, working on new book proposals, online illustration projects and more. “I was talking to my son the other day about some project or talk I was giving, and he said, ‘Dad, why don’t you relax a little?’” Mack says, “but I’m not going to golf. I have always had this drive to draw. It can’t be as manic and insane as it was when I was doing the weekly strips. I’m smarter now, so it’s maturely insane.”

Words by Gillian Kiley

BILL KIENZEL 67 ID FONT QUIXOTE

Nobody embraces iterative design like Bill Kienzel 67 ID. It’s been 40 years since he created SpectraConic, a font that pushes the boundaries of letterforms—full-color with tailored kerning supporting a 3D concept. Four decades later, Kienzel is still engaged in design development, hoping that industry progress and technology will catch up to his cutting-edge idea.

“What a ride it’s been,” says Kienzel. “The pure visual joy of working with such glorious color has been exhilarating. Add to that the satisfaction of hard-won solutions through a lot of reworking. There’s an overall happiness of having given this idea —probably my best one yet—the commitment it deserves.”

That commitment has been driven by design exploration, what Kienzel calls “the higher purpose of art” with gratitude to RISD for instilling the sentiment. He credits the intellectual challenge RISD presented for creative minds, something he feels connects alumni across all generations and disciplines. Kienzel’s career in type design began at Compugraphic, a producer of typesetting systems, in 1974, where he worked in type development and type marketing. “The latter gave me enhanced perspective on using type, as we designed promo- tional materials for their font library,” he explains. In 1979, Kienzel drove his family cross-country for a new position at Information International in Los Angeles. There, he was asked to design their 1981 holiday card, a unique opportunity to try out new letterform ideas in collaboration with their Digital Scene Simulation group, CGI pioneers. This was when SpectraConic was born; the sculptural font heralded “Peace on Earth” in a way no one had seen before.

The result was featured in a May 1982 article, “Type Design Enters a New Age,” in Art Direction magazine. Kienzel’s career took him to the Xerox Font Center and later to the Santa Barbara area, where he contin- ued working on SpectraConic’s design. He developed a Mac-based interpretation in Adobe Illustrator and created extensive documentation about its color structure, letterfit processing and app implementa- tions to chronicle this journey.

After all this time, Kienzel remains unsure if SpectraConic will realize its full potential. And, despite challenges, he’s thankful for the journey. “I have no clue how this effort will result. SpectraConic may earn a happy future—I would be thrilled to see it make humankind more joyful,” he says. “Database quandaries and the limits of color- font formats (it uses 180 colors!) remain obstacles. Maybe I won’t see it become keyboardable, but it already is a cursor-driven lettering system.”

Kienzel describes this legacy project as something he sensed he owed the world. “I was privileged to invest in it all the typographic principles I’ve absorbed from so many respected colleagues in the realm of type,” he says. “I’m grateful to have been entrusted with this special idea.”

Words by Julie Powers

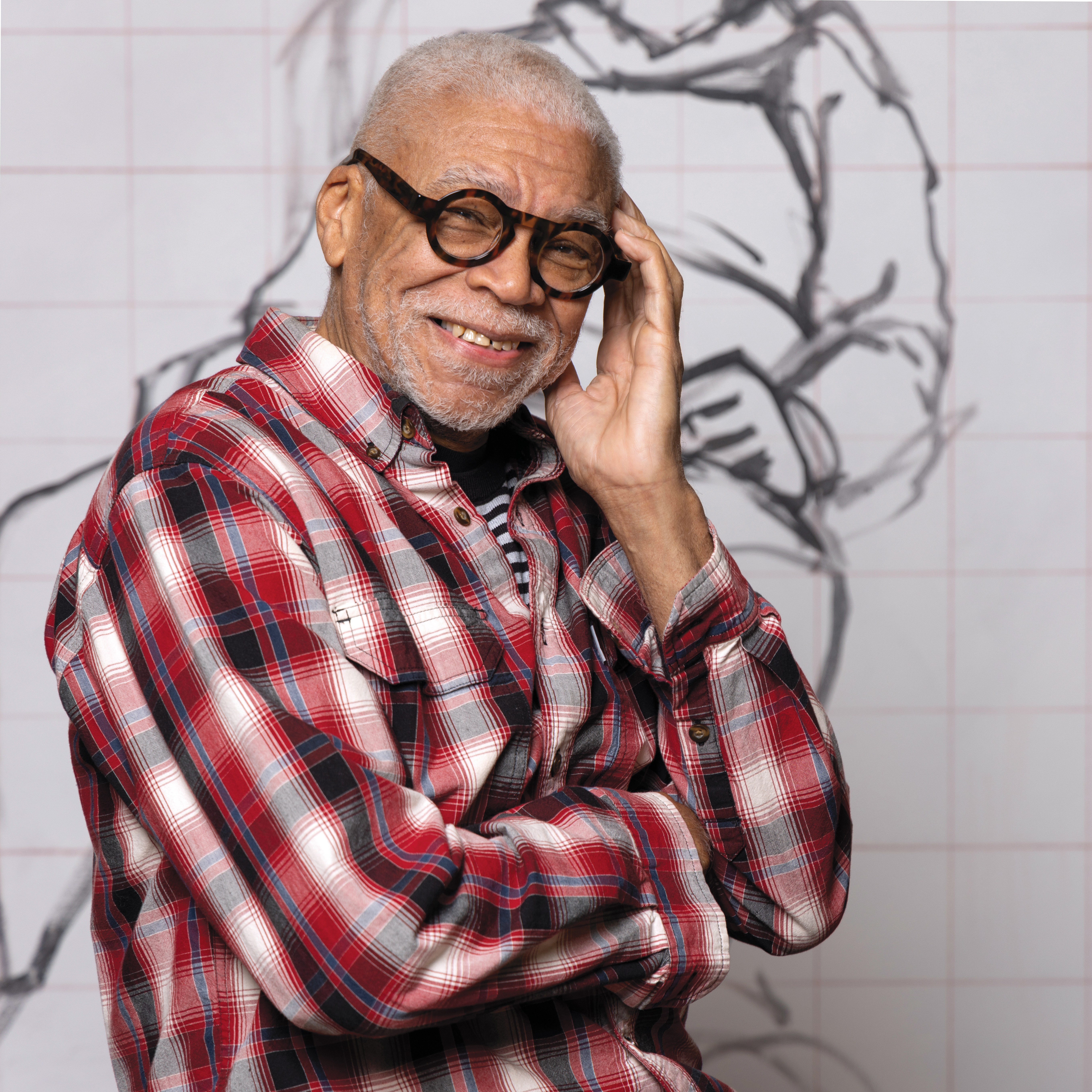

BOB DILWORTH 73 PT PAINTS AT MIDNIGHT

Bob Dilworth 73 PT was participating in critique before he even knew the word. As a teenager, he enjoyed painting and drawing and connected with a faculty member at St. Paul’s College, a Historically Black College in his hometown of Lawrenceville, VA. She became his mentor and engaged him in in-depth conversations about his work that he later came to know as critique. She encouraged him to apply to RISD and he arrived in Providence in 1969 with a plan to be a painter.

Not just a painter, but a rich and famous one at that.

“Boy, did that plan change,” he says, laughing. “Those may be the dreams that drive you, but I quickly learned that a desire to be a maker and creator is what really sustains you. Instructors can teach theory and principles, but you become a painter through your own commitment.”

Dilworth maintained his commitment to painting throughout his 30-year career as faculty at University of Rhode Island, where he taught painting, drawing, design and African American art history. His own work never took a backseat. If that meant waking up at midnight to paint before a day in the classroom, that’s what Dilworth did.

Reflecting on this work, he says, “I like to saturate a painting with a lot of stuff. I’ll add layers of marker, fabric, paint. Sometimes I think something is done, but I’ll revisit a week or a month later and see another opportunity. When nothing more can be added and nothing can be taken away, that’s when a piece is done.”

Lately, Dilworth has expanded his work with fabric, constructing pieces using his father’s ties or jeans and stitching portraits, often of family, atop them.

A recent show at the Fitchburg Art Museum, Bob Dilworth: When I Remembered Home, showcased his multilayered fabric and painted portraits. Several of his pieces are in the RISD Museum’s permanent collection and, in 2024, he was honored with the Rhode Island Pell Award for Excellence in the Arts.

It may not be the fame he had in mind when he arrived at RISD in the fall of 1969. But it is a testament to the dedication and hard work necessary to making a life as an artist. RISD professors showed him the importance of that hard work and he, in turn, showed his students. Dilworth lists Mahler Ryder and John Torres as faculty who made a strong impact on him. They took his work seriously, he says, so he put in serious effort. And he’s been at it ever since.

Words by Lauren Rebecca Thacker

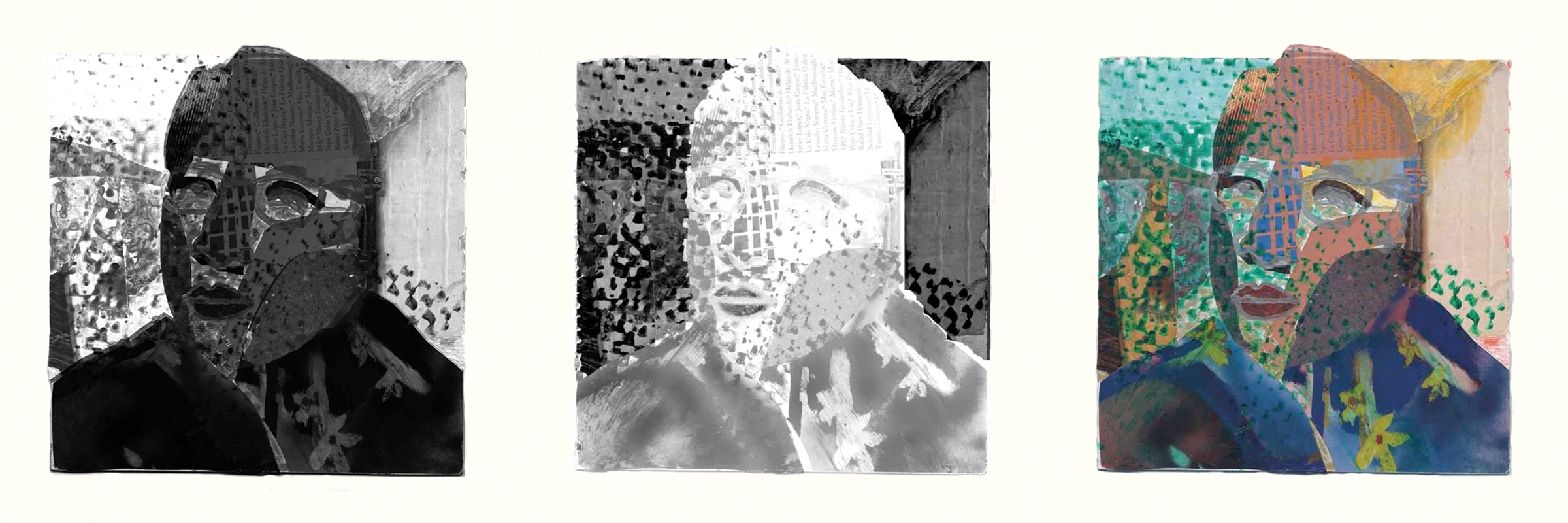

NELL IRVIN PAINTER MFA 11 PT RECONFIGURE AND REVISION

In 2006, as Nell Irvin Painter MFA 11 PT stood at a bus stop in New Brunswick, NJ, her first-year classmate at the Mason Gross School of the Arts at Rutgers University turned to her and asked her age. “Sixty-four,” Painter told the student, who gasped in excitement.

That day, Painter straddled two worlds. She was both a new undergraduate student and Princeton University’s Edwards Professor of American History Emerita. An historian specializing in 19th-century Southern American history, Painter had published widely, won accolades and taught thousands of students not all that different from the young woman at the bus stop. Painter was starting over with a BFA before going on to earn her MFA in Painting at RISD. Then, as now, she is “a painter with feet in both visual and verbal terrain.”

At RISD, Painter was most certainly the only graduate student to be interviewed by Stephen Colbert for The Colbert Report, have a book featured on the front page of The New York Times Book Review and serve as president of the Organization of American Historians during their course of study. Painter juggled critical success, professional recogni- tion, attention to her age from classmates and others and, of course, the demands of her degree programs. Why did she do it? One answer: the pursuit of pleasure.

“Concentrating on what I could see gave me intense pleasure, and seeing what I could make with my own hand and according to my own eye was even more satisfying. Art stopped time. Art exiled hunger. Art held off fatigue.”

Painter has made art since childhood and describes her work, which incorporates found images and digital manipulation, as carrying both discursive and visual meaning. Painting allows her to step away from her career-long search for historical truth and engagement with the politics, particularly racial politics, of American life and “reconfigure the past and reenvision myself through self-portraits,” she says. So in addition to pleasure, painting represents freedom.

In her 2018 book Old in Art School, a chronicle of her Rutgers and RISD years, Painter writes, “More than ever I’m obsessed by age and the desire to un-age,” but her pace of activity and production dispenses with conventional ideas of what one does in their eighth decade. She published the book I Just Keep Talking—A Life in Essays in April 2024, chosen as one of the best books of 2024 by The New York Times, the Boston Globe and Kirkus Reviews. Her work has been featured in numerous solo and group shows and is in several public collections. She has won artists’ residencies and fellowships, and spent fall 2024 as the Mary Ellen von der Heyden Fellow at the American Academy in Berlin.

At the Academy, she worked on My Elsewheres, a personal exploration in images and text of place and identity. Reflecting on the formative years she spent in France and Ghana, and later in Germany, Painter’s project examines how experiences outside of the US shaped her self-understanding, perspectives on race and history, and the value of narrative storytelling.

Words by Gillian Kiley