Cover Story: Time and Place

Do Ho Suh explores memory, migration and the concept of home.

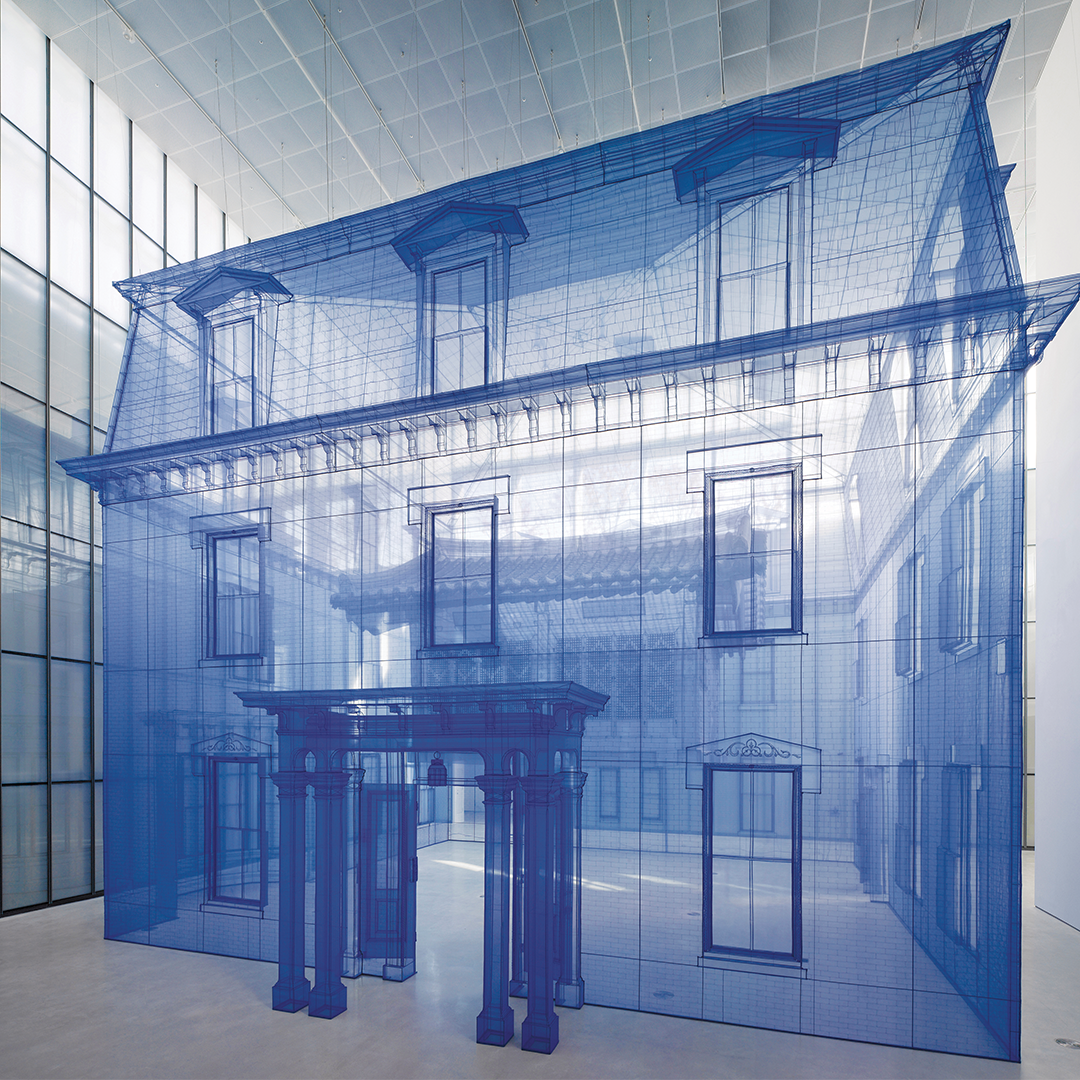

When Do Ho Suh 94 PT arrived in Providence from South Korea to study at RISD, he found a place to live at 388 Benefit Street. A once-grand Victorian mansion, the imposing red-brick building, with a mansard roof and columned portico, had long since been carved up into modest student apartments, one of which became Suh’s first home in the US.

“That building still features in a lot of my work,” says Suh, one of today’s most prominent Korean artists, best known for translucent fabric sculptures that recreate buildings he has lived in while exploring ideas of memory, displacement and home.

Suh rose to international attention when he repre-sented South Korea at the Venice Biennale in 2001 with a site-specific installation that elevated the floor of the gallery and invited visitors to walk on glass panels supported by 180,000 cast plastic human figures. Since then, his installations, sculptures and drawings have been exhibited and acquired by major museums worldwide.

In 2008, Suh created Fallen Star 1/5, a model of his childhood home in Korea colliding with a replica of his Providence apartment. Four years later, he perched a pale-blue clapboard cottage precariously atop the engineering building at the University of California, San Diego, alluding, he says, to his own sense of disorientation when he first arrived in the US.

Suh is currently the subject of a major exhibition, Do Ho Suh: Tracing Time, now on view at the National Galleries of Scotland in Edinburgh through September 1. The exhibit brings together more than 100 of Suh’s works from the past 25 years and is the first exhibition in Europe to explore the role of drawing in his artistic practice.

It was while living on Benefit Street, as a way of adjusting to the discomfort of his new environment, that Suh began two practices that have underpinned his art since. “I began to measure my space, and soon, whenever I moved to a new space, I produced paper rubbings of the interior,” he says. The measuring was particularly tough, he says, since he had to convert from metric to imperial in his head as he went along. “It was a breakthrough to find a dual-unit tape measure at the amazing Adler’s on Wickenden Street! I was so happy to revisit the store when back last year [to receive an honorary degree from RISD].”

By the time he began studying at RISD, Suh—whose father, Suh Se-ok, was one of Korea’s best-known ink painters—had already earned both a bachelor’s and a master’s degree in traditional painting from Seoul National University. This was an essential foundation, he says, but he began to break free of its strictures during his MFA, creating freestanding folding screens that challenged the idea of painting in a traditional Korean context. “It was also a play on the use of folding screens in East Asia,” he says, “which were often used to create a particular landscape background—I loved the idea of making a place portable or moveable. A lot sprung from that.” The experience also solidified his need to expand as an artist. Hence the move to the US.

At RISD, during the early ’90s, Suh’s ideas began to coalesce around the relationship between architecture and clothing. “I was reflecting on this endless ritual, which starts from birth, of moving in and out of your clothes and built environments,” he says. “Once I had moved into a Western building in a Western context, I began to think about this movement as a series of tiny displacements. But I felt oddly prepared for it, because Korean architecture is traditionally much more porous than [architecture] in the West—walls are made of rice paper and you reconfigure the space throughout the day.”

As he began his MFA at Columbia University (he transferred after a year to Yale), Suh became absorbed with ideas of site-specificity and transportability and created a heavy muslin cloth sheath for the inside of his student studio space in Morningside Heights to recreate the bedroom of his childhood. “I then ‘undressed’ the room and presented the muslin as an empty shell,” he says, “like the shed shell of a cicada.” When he sewed his first translucent fabric “home” in Korea a few years later, he was able to pack it into two suitcases and fly back to the US with it.

Although his art has explored many innovative avenues in a stunning variety of media, it is the ethereal architectural fabric pieces—of 388 Benefit Street, of the traditional hanok house where he was raised in Seoul, of his Chelsea apartment in New York City, of his flat on London’s Union Wharf—that have become his most celebrated pieces.

“They’re often very ordinary domestic spaces that people can relate to,” says Suh, attempting to explain their appeal. He can see why viewers find the vivid colors and diaphanous fabrics seductive, but that is also something he has struggled with. “I didn’t set out to make a beautiful, alluring sculpture,” he says. “I was interested in the conceptual possibilities of using a transportable, translucent fabric for something we think of as solid. It’s metaphorical, and some of the visual impact is, for me, almost a by-product.”

The rubbings that Suh began in Providence have also continued as a way to explore and discover his living spaces. To create them, Suh affixes thin paper sheets over every inch of the interior walls—light switches, cabinets, door handles, refrigerators, even the bathroom sink—and then rubs across the paper with graphite, colored pencils or his fingertips to create an impression on the paper. The rubbings can help him understand the dimensions of a space better in preparation for the fabric pieces, or they can exist in their own right as photographed works of art.

Rubbing is an act of devotion for Suh. The process, he says, is intensely physical—“You have to apply exactly the right pressure, not too little, not too much, and maintain it carefully”—and also a meditative act that can unearth long-forgotten memories. That was certainly the case when Suh undertook to rub every surface of his longtime, much-beloved apartment in New York City, a project that expanded to include the entire four-story townhouse and took two years. “It remains a very interesting process to me, and exhausting,” he says. “I completely lost my fingerprints when I was doing that project.”

At the heart of his current exhibition are works on paper. Through drawing, says Suh, he can thrash out complex ideas and ruminate about ideas around movement and personal-versus-collective space.

Ever since he first arrived at RISD, he has carried small sketchbooks “religiously,” the same images recurring over three decades.

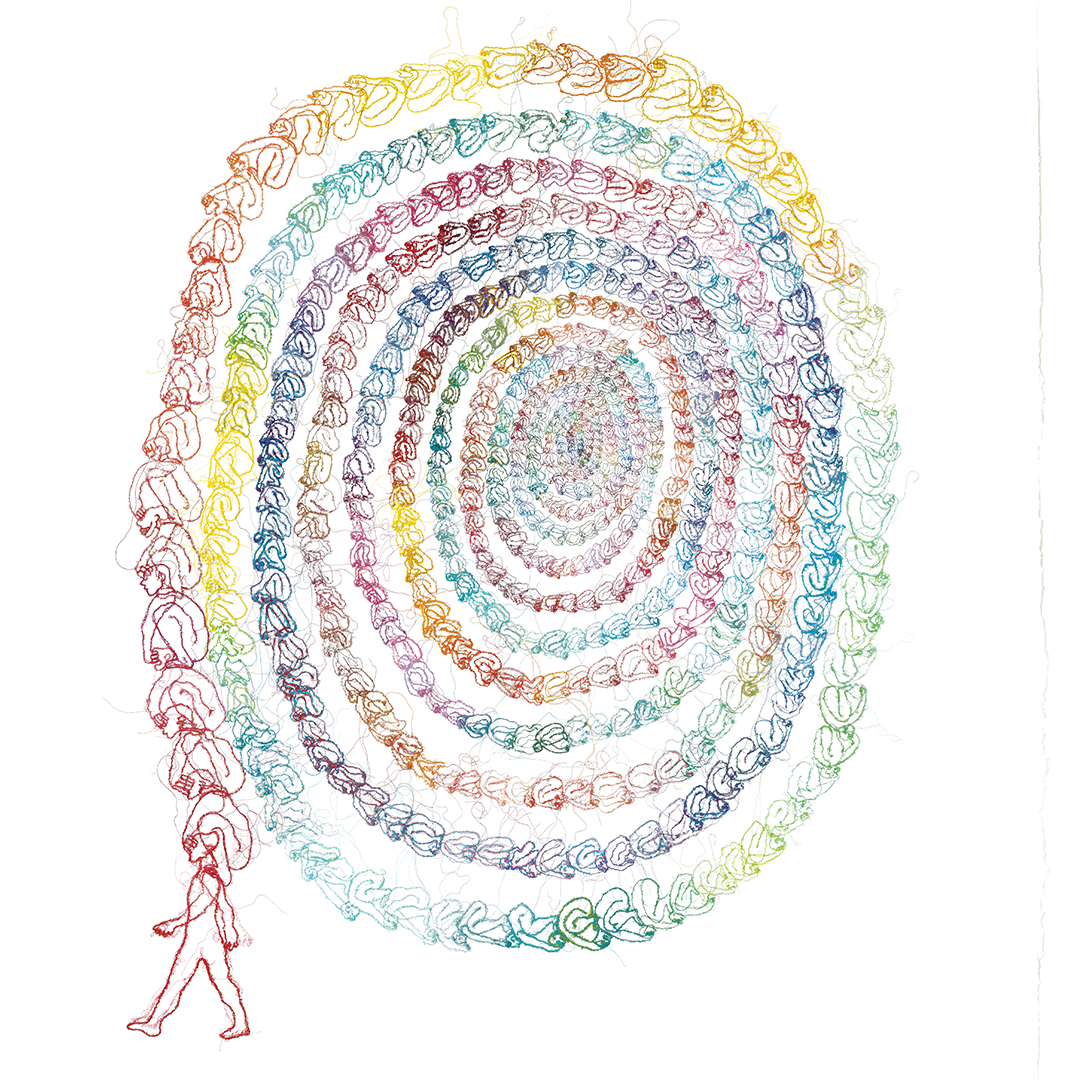

In 2009, while on a residency at STPI Creative Workshop & Gallery (formerly Singapore Tyler Print Institute), Suh began to experiment with the sculptural possibilities of paper, which led to his thread drawings. They are made by sewing onto gelatin sheets and then dissolving the gelatin in a water bath so that the stitching becomes embedded in paper pulp and the threads emerge as a shadowy image. “I then move the loose threads into the positions I want them in,” says Suh. “You have to work very fast and carefully, but it’s a very organic process.”

Collaboration is central to the practice, says Suh, who credits the STPI team and their innovative approach with making these pieces possible. At his studio in London, where he lives with his wife, Rebecca Boyle Suh, and their two daughters, Suh works closely with a team of architects. “I’m invested in doing away with this idea of the isolated artist ‘genius’ beavering away on their own in a studio,” he says. “I couldn’t realize most of my projects alone.”

London feels like home to Suh these days, since that is where his children were born and where his family life is rooted, but he is interested in the “portability or otherwise of the concept of home.” He misses New York—Chinatown’s soup dumplings, Chelsea’s gallery evenings—and ponders the question of home in relation to the three cities that have figured large in his life. His Bridge Project centers on a bridge (literal and metaphorical) that links London, Seoul and New York. At its center, which happens to be in the Arctic, is the so-called “perfect home.” “It’s a wild thought experiment,” says Suh, “but I find it very grounding.”

Recently, Suh has been making work with the assistance of architectural modeling programs. One piece features a large, robotically engineered sculpture of Home Within Home, an earlier work that involved the Korean hanok house being engulfed by the Benefit Street house. “It will be installed so that some of its threads, which are extruded by the robot, feel like they’re burrowing through the museum walls. I want it to feel like a sort of parasite or growth within the gallery space,” says Suh.

Suh is also working on a kinetic version of Public Figures, a 1998 work that features a stone plinth supported by the outstretched arms of hundreds of miniature fiberglass-and-resin figures. The piece was always intended to move, says Suh, as a counter to the idea of static monuments.

Circling back to his New York rubbings project, Suh is realizing long-held plans to resurrect his apartment rubbings, which he has kept in storage, carefully numbered, since the building was sold, and mount them on frames to build a scale model of the brownstone interior for a future museum exhibition. “It’s technically very challenging but I am so excited to finally do it,” says Suh. “I’m not a particularly fast artist. My projects are often very complex and take years to R&D and then make, so I have these same works and series that thread through my practice from the beginning.”

Lead image: Fallen Star 1/5, 2008–2011, ABS, basswood, beech, ceramic, enamel paint, glass, honeycomb board. ©Do Ho Suh. Courtesy of the artist and Lehmann Maupin, New York, Seoul and London. Photo by Jeon Taeg Su

Words: Judy Hill