Living the Dream

The New Yorker cartoonist Roz Chast plumbs the absurdities of everyday life, sleeping and awake.

Roz Chast 77 PT hates to be bored. The renowned cartoonist keeps ennui at bay by always having a slew of projects on the go in her Connecticut studio—from egg painting to rug hooking to ukulele playing—not to mention the weekly batch of sketches she submits to The New Yorker magazine, which, since 1978, has published more than 1,000 of her off-kilter musings on everyday life.

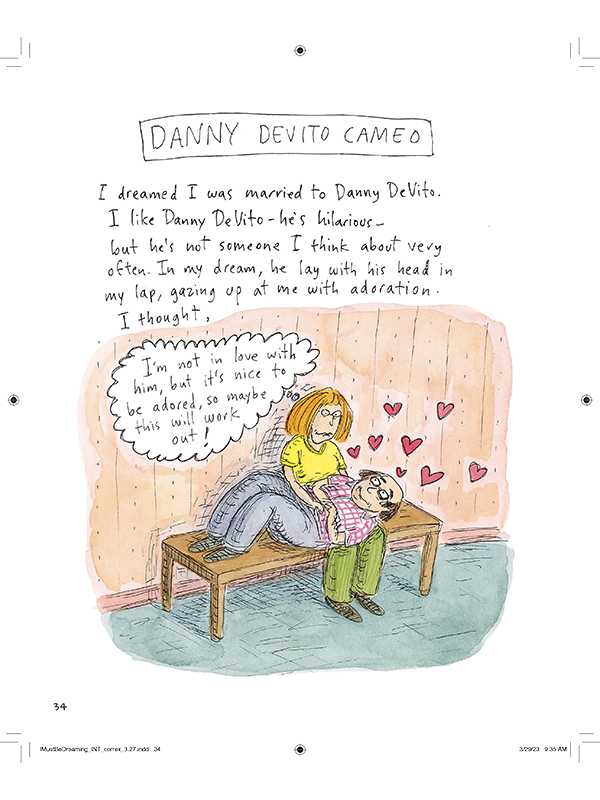

Chast also hates to bore her loyal fan base, which is why, in her latest graphic book, I Must Be Dreaming, she offers readers what she calls “dream filets” that hone in on moments of peak dream hilarity.

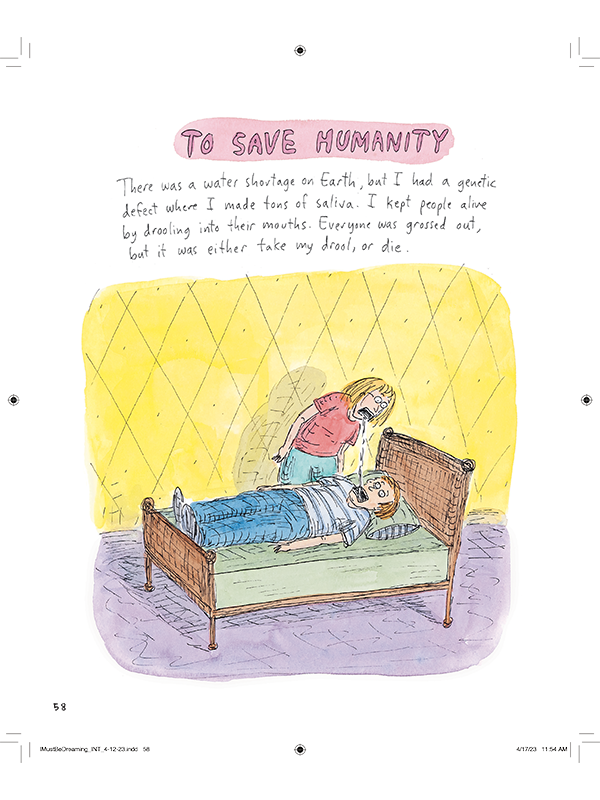

A sampling of said filets drawn in Chast’s singular style are: a woman licking whipped cream off a bald man’s head; Chast telling writer Fran Lebowitz to “give a hoot and a holler” if she’s ever in her neighborhood; two rotting plums devouring each other and bursting into flames; actress Glenn Close covered in thousands of baby spiders; Chast keeping people alive during a water shortage by drooling into their mouths, with a caption that reads, “Everyone was grossed out but it was either take my drool or die.”

Chast has been interested in the landscape of dreams since she was a child growing up in the Flatbush section of Brooklyn. “It just seemed like such a strange and inexplicable sort of experience that you’d go to sleep and you could fly,” she says. Her new book includes a smattering of dream theory—Freud, Jung, the Kabbalah, et al.—but at its heart is an exploration of Chast’s sleeping mind, with dreams as idiosyncratic (by turns fantastical, profound and pedestrian) as ours, but somehow a whole lot funnier.

“I think the first one I [drew] was about my mother meeting this guy who, for some reason, was named Bissell,” says Chast. “That could be because there was a drugstore in our town named Bissell. In my dream he had somehow gotten ahold of O.J. Simpson’s glove and he was showing it to my mother and telling her that he had this business idea where he could rent out the glove for parties. I drew it up and put it into four cartoon panels and it was very fun to do.”

While she was working on the book, Chast wrote down her dreams every morning as soon as she woke up. You have to, she says, or they will disappear. Even so, some are elusive and come back only as fragments during the day. Chast calls these “dream hangovers,” and the book includes a few of the “ones that got away”—a cult of corpulent men in France who dress like Liberace but sound like Johnny Cash (singing “Prison de Folsom”), a can of food called Bungalow Breakfast, a leprechaun with a unibrow. Jotting ideas down in a notebook is second nature to Chast. “Things will just sometimes seem funny,” she says, and provide inspiration for a cartoon. Riding on a train a while ago, “not even thinking of cartoons,” Chast caught sight of a poster. “It was for Carvel and there was a little girl wearing glasses with a party hat on, surrounded by family and friends and grandparents.

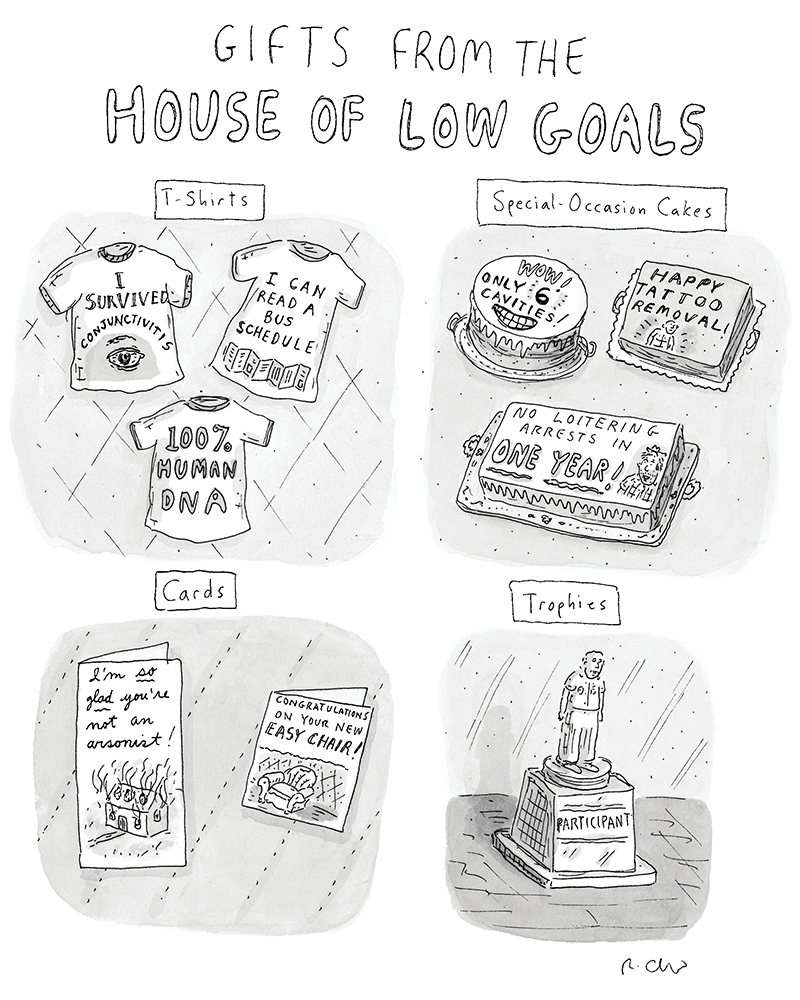

On the cake was written, ‘Congratulations on your new glasses,’ and I thought, ‘Well, we really have set the bar pretty low.’ And that became a cartoon—Gifts from the House of Low Goals.”

Chast’s take on the world around her, which pokes fun at our insecurities and foibles while eliciting a heaping dose of compassion for those same frailties, emerged out of a childhood during which she often felt like an outsider. As chronicled in Can’t We Talk About Something More Pleasant? Chast’s 2014 graphic memoir about taking care of her ailing parents, her childhood—with a domineering mother and an intensely anxious father—was less than happy.

“I did well in school because my parents were teachers and I sort of didn’t have a choice,” she recalls. “But I hated it. I was not good at sports. I was not social. I didn’t like other people, and you know, they didn’t particularly like me. I wasn’t pretty.I didn’t know how to flirt.”

One thing the young Chast did have going for her was a love of drawing and the positive attention that garnered. “Since nursery school I remember being praised for art that I did,” she says.

When it was time to think about college, Chast chose to attend a liberal arts school (Kirkland College, in upstate New York, which closed in 1978) where she could take “all art classes” but still get a BA. “My parents did not want me to get a BFA,” she says. “To say I wanted to be an artist or a cartoonist, that would’ve been like saying I wanted to be a tightrope walker or juggle for a living. It just seemed like an insane thing.”

After two years, with the encouragement of a printmaking teacher at Kirkland who recognized her talent, she transferred to RISD. And that, says Chast, was when she began to doubt her artistic ability for the first time.

“At RISD, suddenly I was surrounded by people who were all very dedicated to being artists,” she says. “They weren’t dilettantes, they were serious artists, and it was very daunting.” Because there was no cartooning department, she started out as a graphic design major but was “terrible at it, just terrible, way too messy.” Next, she tried illustration, because it was closer to cartooning, but again “it was not cartooning.” Finally, she hit on painting because she lived with painters and “wanted to love painting more than I did.”

Ultimately, though, she says, “I came into RISD as a cartoonist and I left as a cartoonist.”

And that was no small feat considering the setbacks she experienced. On learning there was a group of male students who had started a cartoon publication called Fred, Chast eagerly submitted sketches but was rejected. That remains a terrible memory. “It was shocking. It was painful. I cried. The whole nine yards of tragedy.”

As Chast tells it, she floundered for her first couple of years at RISD. “I lost complete faith in what I was doing,” she says, though in retrospect she sees that ordeal as a “really good thing” because of how it equipped her for postcollege life.

Chast knew how different her work was from the prevailing cartoon aesthetic, which favored a meticulous illustration style and witty one-liners. Chast’s work, by contrast, featured amorphous “blobby” characters populating busy scenes that thrummed with anxiety and spewed a cacophony of speech bubbles, captions and insets scrawled in an unsteady hand and liberally peppered with underscores, exclamation points and asterisks.

As Chast began taking her cartoons around to publications, she thought she stood a chance with The Village Voice because they published Jules Feiffer, Mark Alan Stamaty, Stan Mack and other cartoonists whose work had a more narrative bent, and she did indeed sell some cartoons there.

The New Yorker felt like such a long shot as to be almost absurd. But with a devil-may-care insouciance that might surprise Chast fans, she presented her work to then-comics editor Lee Lorenz, who decided to take a chance on her. Less than a year after graduating from RISD she had her first cartoon purchased and soon after she was put on contract with the magazine.

“It still seems unbelievable to me, and I’m still incredibly grateful,” says Chast, noting nonetheless that some of the “old guys” at the magazine really hated her work. Lorenz told her later that one of them asked him if he owed Chast’s family money.

For Chast, 45 years later, the enduring appeal of cartoons has a lot to do with the way text and illustration are intertwined—each vital to its impact—and how the medium lends itself to making fun of American culture. Some of the earliest cartoons she remembers gravitating toward as a child were in the pages of MAD magazine.

Even if she couldn’t have explained exactly why, at the age of 11 many of the commercials, sitcoms and variety shows she saw on TV struck her as “inane or just plain weird.” And then, she says, to see them lampooned in MAD magazine, “was like, ‘Oh my God, there’s other people who see it too.’” She remembers a parody of Chase & Sanborn Coffee she came across in the magazine. “But instead of Chase & Sanborn, it was Cheese & Sandbag. I don’t know why, but that cracked me up. I would be in school and start thinking about it and I’d just start to giggle to myself.”

Other early influences included Charles Addams, who she describes as “jolly but transgressive,” as well as George Booth, Ed Koren, Helen Hokinson and Mary Petty, all of whom, she says, drew from a very particular, personal point of view and created “whole worlds,” not just talking heads and funny lines.

Chast herself may be the queen of creating whole worlds, and she especially loves drawing interiors replete with detail, so the coffee table is never just a coffee table but a repository for a bowl of coffee candies, a half-finished cup of tea, a slightly sad vase of flowers, and three or four remotes, each one a little different from the other.

She is more interested in drawing people, invariably of the schlubby variety, than trees, and despite having lived in Ridgefield, Conn., for more than 30 years, professes a lingering unease with suburban life and its rituals, such as driving cars and spending time in nature.

After the runaway success of Can’t We Talk About Something More Pleasant?, which spent 100 weeks on the New York Times bestseller list and won a National Book Critics Circle Award, Chast treated herself to a studio apartment rental on the Upper West Side, close to where she had lived with her husband, humor writer Bill Franzen, before their growing family prompted the move to the suburbs. She visits every week or so.

In the city, she says, she feels comfortable and grown up and not in the wrong outfit. “It’s still the only place I’ve been where I feel, in some strange way, that I fit in. Or maybe, that it’s the place where I least feel that I don’t fit in,” she explained in Going into Town: A Love Letter to New York.

Not much else has changed in Chast’s life, though, since becoming a bestselling author. And she’s fine with that.

“It’s always nice to do a project that peoplerespond to in a not-throwing-tomatoes way,” she says, “but I’m still submitting cartoons every week to The New Yorker and I haven’t bought a private jet. I would have to park it in our backyard, I guess, which probably wouldn’t go over well with the neighbors. Plus, there’s a slope in our yard, and, I don’t know, it’s complicated. It just wouldn’t work out too well.”

Roz Chast portrait by Bill Hayes. Words by Judy Hill.