The Kids Are Alright

Brian Selznick talks about his latest book and how Steven Spielberg inspired the story.

Imagine one day you get a call asking if you’d write a movie for director Steven Spielberg. That feeling in the pit of your stomach, that pounding of your heart? That’s exactly how Brian Selznick 88 IL felt when he answered the phone.

The movie, as Spielberg originally envisioned it, would be about nature from nature’s point of view, with talking, singing and dancing plants. Did anyone want to watch a movie about dancing, singing plants? Selznick had his doubts. But what he enthusiastically said on the phone was, yes it was a brilliant idea, and he hopped straight on a plane to meet with the legendary director.

He dreamed that despite his nerves, he would hit if off with the man who made the greatest films of all time, and they would both agree that this particular movie shouldn’t be made.

And that’s mostly how it went. The two men sat at a conference table with producer Chris Meledandri in Spielberg’s office, below the sled from Citizen Kane, swapping ideas that tumbled into memories that turned into thoughts that became more ideas. When the meeting ended, Selznick found himself back on a plane headed home with an assignment to work on the screenplay for a month.

“I panicked, because that wasn’t how the meeting was supposed to end ... I came up with ideas that Spielberg found exciting and pleasing that then sparked other ideas in him ... and suddenly I had to do this movie,” says Selznick.

Over the course of the next year, Selznick began to figure out how to tell this story. Spielberg originally wanted it to take place before the dinosaurs existed, when the world was mostly covered in ferns. Selznick moved the setting up a couple hundred million years so that people leaving the theater would have fallen in love with a world that looked more like our own.

“Spielberg loved that idea. I must say it’s very thrilling to present an idea to Steven Spielberg and have him love it,” says Selznick.

The movie was shaping up, but sadly so was COVID-19. The pandemic eventually derailed the plans for the film entirely, but Selznick, the reluctant writer, was now attached to the project. He proposed one last idea—that he continue writing the story, but as a book, not a screenplay.

Thankfully, Spielberg agreed.

The end result is Big Tree, which hit shelves in April of this year. The book tells the story of two seed siblings—Louise, who looks to her dreams for guidance, and Merwin, the parentlike rule-follower—who are suddenly thrust into the world to find a place to grow after a tragic split from their mama tree. Amidst a larger, obvious message about the need to save our environment is a more subtle exploration of the common, internal, adult struggle of whether we listen to our head or our heart.

“I wasn’t conscious [of that] when I was writing this. I was only conscious of writing these two characters who needed to be in conflict with each other. But I realized that it’s me telling the very loud, rational, frustrating part of myself to chill out a little bit and let the irrational, dreamy side take control more often,” says Selznick.

In many of his books, Selznick realizes long after they’re finished that he’d subconsciously been writing about himself.

“I often realize that most, if not all, of my characters are me in some fashion,” he says.

He gives the protagonists his interests, which range from Deaf culture to the history of museums, in the hope that the reader will care about the characters and, by proxy, care about their interests. His main characters are always children who are separated from their parents in some way. Although the orphan is a familiar children’s book trope that thrusts young people into an adult world where they are forced to make decisions and act independently, it’s also perhaps a means for Selznick to resolve the complicated relationship he had with his own father.

The eldest of three children, Selznick grew up in New Jersey. A gifted artist, he always felt supported and encouraged by his parents, but not always understood. Although he describes his childhood as “pretty happy” and void of “any real direct tragedy,” it was also quite isolating. At the age of ten, not coincidentally the age of many of his protagonists, he underwent major surgery on his chest.

“My sternum was born with a concavity that was causing severe pain when I had asthma attacks. I had this very intense relationship to illness as a child,” says Selznick.

Selznick was also a queer kid in a suburban town (although he didn’t know that’s what he was at the time) when there was little media representation of queerness or public support. His father, an accountant and a sports fan, shared little in common with his son.

“There was a sense of him being absent from a part of my life that probably parallels some of the things that I write about,” says Selznick.

His father died just before Selznick began writing The Invention of Hugo Cabret, the book that shot him to literary fame and also became an award-winning film directed by Martin Scorsese. Before his father’s death, they were on good terms and his father even met Selznick’s husband. In short, things turned out OK. Although this isn’t always how real life goes, it is true of the world Selznick creates for his characters.

“I want to be able to say to young people that life is going to be scary. Feeling scared is normal, and difficulties don’t come to an end, but there is safety at the end of the road,” says Selznick.

He doesn’t give his characters any special powers or magic to navigate the unique situations they find themselves in. They’re normal people in extraordinary situations who unearth the necessary bravery to survive. And along the way, they create the families they need.

Selznick received a final phone call from Spielberg when Big Tree was published. This time Meledandri was on the line too. They wanted to congratulate him on the book and tell him how much they loved it.

In the end, the movie with talking, singing and dancing plants didn’t get made after all. But for Selznick, that’s OK. He realized that perhaps all along this was supposed to be a book, one that he could fully envision and draw, and not simply words on a page handed over to animators.

“With Big Tree, I’m very happy that there was this very unusual situation that led to the creation of the book,” says Selznick. “It’s strange that I ended up feeling very much that this is what it was really supposed to be.”

Selznick came to campus last June 2 for an event co-presented by the Fleet Library and the Alumni Association.

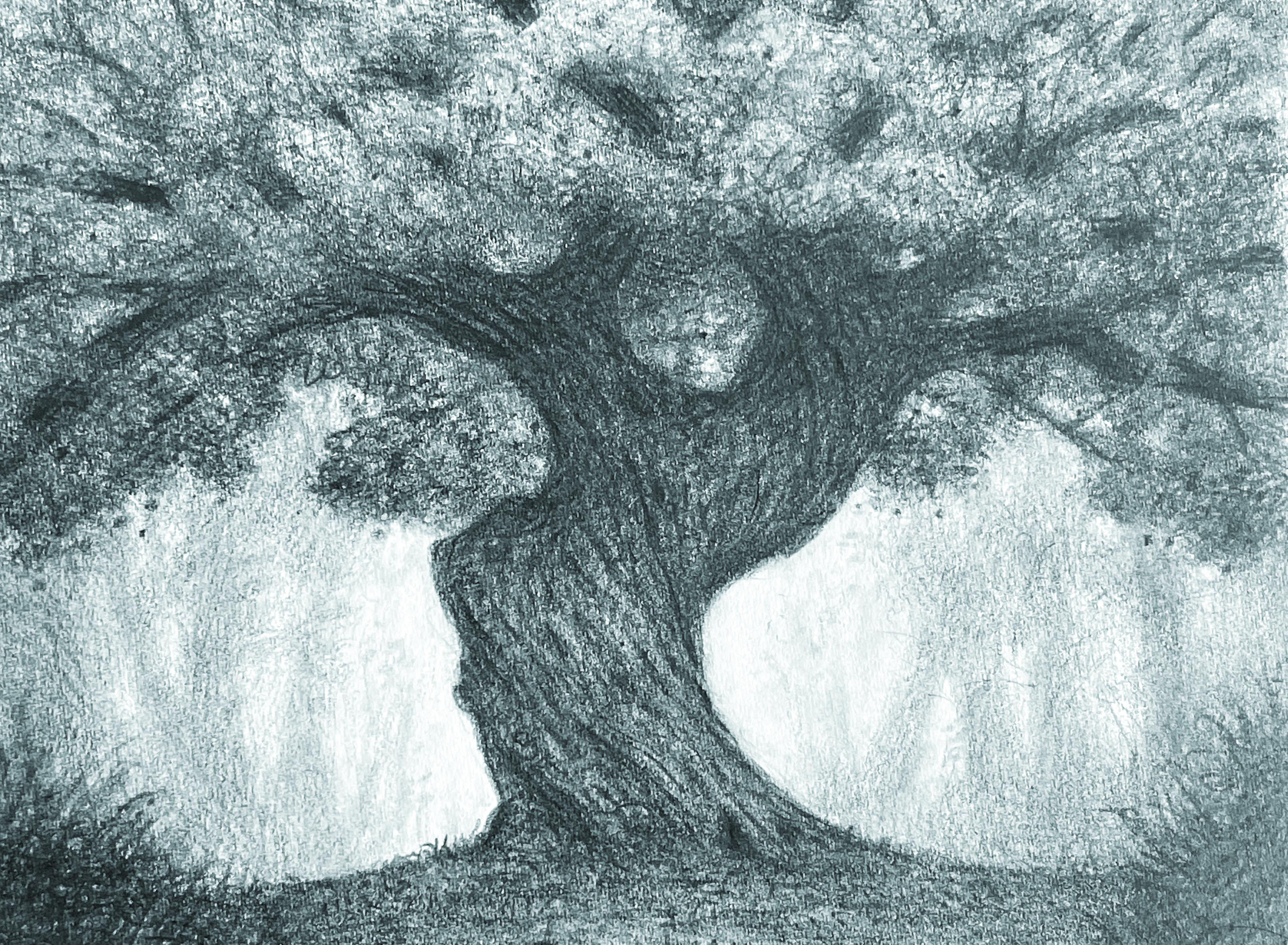

Words by Abby Bielagus. Selznick’s drawing of Mama tree, a character in Big Tree