Give Peace a Chance

Design to enhance global security.

While the nuclear threat is not top of mind for most Americans, Russia’s war in Ukraine has once again brought the issue back into the spotlight. And it is a strong focus of Tom Weis MID 08, an associate professor in industrial design at RISD and founder and partner of the Altimeter Design Group.

Design can’t directly enhance global security, Weis likes to remind his students, but his work helps people who are on the front lines of that mission do their jobs better.

Weis’s workshops “shift the dialogue between individuals and organizations on nuclear security that can often get stuck in a stagnant, us-versusthem mentality,” said Elizabeth Kistin Keller, an Oxford-trained researcher and an interdisciplinary problem-solver at Sandia National Laboratories in Albuquerque, New Mexico.

At Sandia, Weis and the Altimeter Design Group, in collaboration with subject-matter experts within the lab, developed a role-playing exercise to simulate the Texas power-grid failure in 2021. The participants took on roles of leaders in areas such as local government and infrastructure. Kistin Keller said such exercises “help us continuously improve the ways in which we are able to apply advanced technologies and technical expertise to avoid, mitigate and recover from disruptions to critical infrastructure.”

Weis consults with even larger institutions, including the United Nations and the International Atomic Energy Agency.

“Some of these organizations were born out of the 1950s, and the world is moving much faster than what their systems had been designed to understand or operate within,” Weis said. “So part of our approach is to leverage the creativity and experiences that participants might have but don’t always get to use in the workplace.”

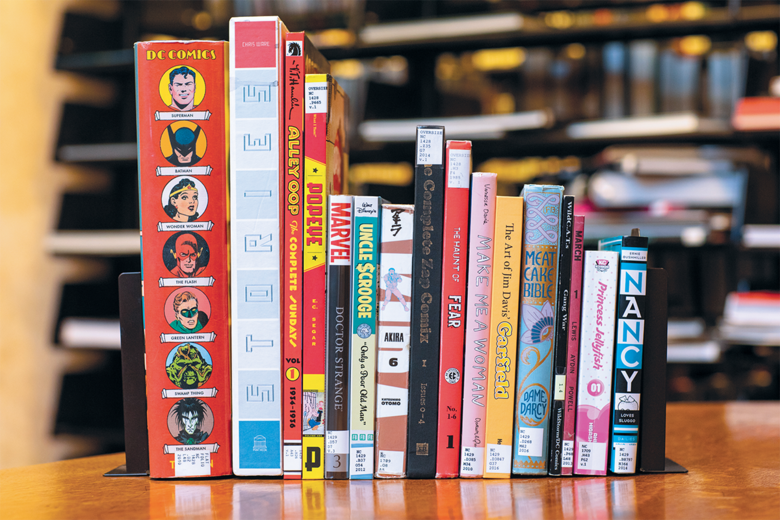

One simple approach can be likened to play: the observation and manipulation of objects.

“Design can activate conversations by bringing ideas to life. Sometimes this takes place through objects, role-playing or facilitated activities. This approach can offer something tangible to respond to that is often insightful in unexpected ways.”

An example is when Weis had his students create a “go bag” filled with things they might need if forced to leave their home on a moment’s notice. Curating these objects personalized what security meant.

“We relate and communicate to the world around us through objects that we purchase, collect, discover or have been gifted. Throughout every stage of our lives, we curate items that signal what we value, cherish or identify with,” Weis said. “These go bags forced students to think about what is truly necessary.”

Weis began to focus on global security after attending a PopTech conference in Camden, Maine, in 2015, when he realized that the nuclear threat had faded from the consciousness of most Americans. PopTech describes itself as “a global network committed to the vanguard of emerging technology, science and creative expression.”

“Speakers did a really great job of using visuals to help communicate both the proximity and the scale of the nuclear threat.” That included the speakers tossing a grapefruit, which stood for how much nuclear material would be needed to destroy a city.

Working with the UN

Weis’s collaboration with the United Nations focuses on the arm of the UN that works to prevent and end armed conflict.

Martin Waehlisch, an officer in political and peacebuilding affairs at the UN, said Weis’s work is aimed at sparking new ideas within the massive organization. Design thinking is common in the private sector, but not in the public sector, where solutions often follow past trends rather than looking forward.

Thanks to RISD, “We don’t just say, 'Let’s be creative, let’s be innovative.' We find the method that allows us to have a concentrated and more systematic engagement on change, on design, and on reshaping the means and ways that we use to address international security issues,” Waehlisch said.

A video produced by the UN that documents its work with the Altimeter Design Group and RISD shows instructors guiding UN officials in what looks something like play, such as examining pieces of art, manipulating objects and kneading clay; the tasks spur conversation. At one point, the workshop participants handle a miniature Greek pillar and share what it means to them. An Asian woman said it represented an institution; a man said: “I’m Pakistani and I’m Muslim. A Greek pillar doesn’t represent institutions to me.” It was an exercise to break the way people at the UN think—the tasks reminded the participants that people have different cultural biases and frames of reference.

“The aim was not to create world peace; the aim was [to learn] how to spot innovation for change in a very, very complicated organization. It’s a long shot to say that all of this leads to better peace processes. But those kinds of exercises strengthen our ability as an organization,” Waehlisch said.

Weis said the success of his efforts to bring design thinking to organizations focusing on security is measured by the fact that his clients are signing up for more of his services and that students are attracted to RISD courses that use his concepts.

Weis recalled that the IAEA was “the toughest crowd” he had to win over.

“They wanted to have these creative sessions, yet they could not unbolt the tables from the floor; the furniture was designed for a leader-driven process, where there’s someone up front speaking,” Weis recalled. The bolted tables were a metaphor for the groupthink that had cemented itself in the agency.

However, “two years later the IAEA said, ‘We have three rooms for you to completely transform,’” Weis said.

Words by Tom Kertscher